It’s midnight in New Delhi, and Twisha Singh is still teaching. She’s often awake until three in the morning assisting students halfway around the world in Montreal.

Singh is a doctoral student in history at McGill and spent much of last year in Quebec under lockdown, worrying about her parents in northern India. When travel restrictions eased this past January, she flew home.

“As a single child, my parents lived alone. I am happy I am with them now,” says Singh, who is pursuing her PhD remotely while caring for her parents.

Since the start of the 2021 winter semester, Singh has been Zooming with her students. She appreciates the flexibility of teaching online. The transition to online learning has also allowed her to juggle between doing fieldwork in India and her work as a teaching assistant. But, it does come with challenges.

There are days when her students don’t even show their faces.

“You talk to black screens and you cannot see whom you are talking to. I definitely miss teaching with actual people in it,” Singh said.

She has also been facing difficulties with her research. Archives around the world had closed their doors during the lockdown. While the restrictions in Delhi have eased up a bit, she is only able to access them on certain days.

With talk of another wave of COVID-19 cases hitting India, Singh says that “there is a lot of uncertainty. I think within a month or two the archives will close again.”

Amid border closures and the shift to distance learning, international students in Quebec have been hit hard by the pandemic. As learning moves online, some have felt the double punch of low morale and financial stress.

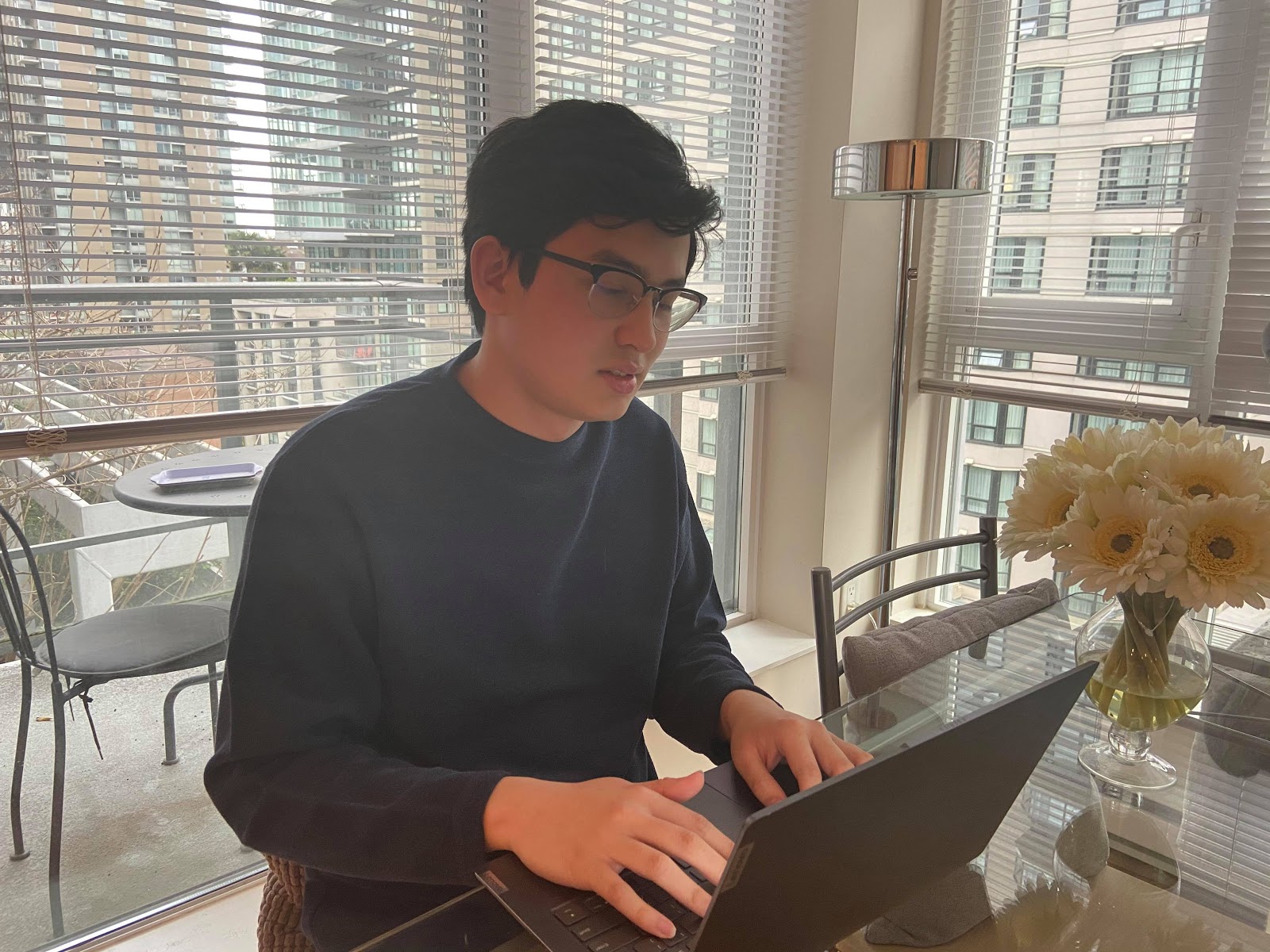

“It’s so easy to feel disconnected from the university,” says Alec Regino, a Masters student from the Philippines studying sociology at McGill. He misses face-to-face interactions in the hallways between classes —and having a normal social life. Communicating with his professors is also more difficult.

“We are reduced to reaching out via email and hope that they are available to respond to you. Some professors are great at that, but a lot of [professors] aren’t,” he says.

Financial stress exacerbated for international students

While online learning can be alienating, money is a greater source of anxiety for Regino. While completing his bachelor’s degree, he was able to take on a couple of jobs on campus while receiving support from his family to pay off his tuition. But when he started his Masters program in 2020, just as the pandemic struck, he was hit by a fee increase of around $3,000 per semester.

“It irks me that my tuition increased by an exorbitant amount and I have to do the program entirely online,” says Regino.

One of the main reasons he opted to study in Quebec was that international tuition fees had been regulated and were more affordable than elsewhere in Canada. That changed in 2018 following a decision by the Quebec government to give universities free rein over how much they charge foreign students.

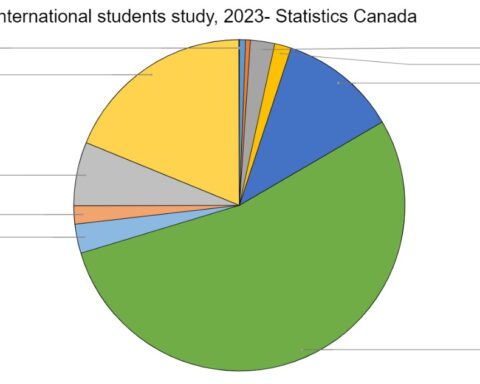

To make up for shortfalls in public funding, universities in Quebec, as in the rest of Canada, have come to depend increasingly on revenues from international student fees. They have more than doubled since 2009. International tuition fees in universities like McGill are today up to five times higher than the domestic student rate and have not gone down despite the transition to distance learning.

Foreign students who have registered at Canadian institutions —but find themselves stuck in their countries of origin as a result of pandemic-related restrictions— still pay the same tuition.

Jade Marcil, president of the Quebec Students’ Union (UÉQ) believes this is unjust and hopes that the pandemic will encourage new thinking around regulating Quebec’s universities.

“Universities should step in to ensure that international students have access to financial aid,” Marcil says, noting that international students did not have access to the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB). The CESB was a federal financial assistance program for Canadian students that ended in September 2020.

In the context of the health crisis, Marcil stresses the importance of reducing extra costs, such as gym fees, to limit the financial burden on all students.

Singh says that the pandemic has caused her a lot of financial stress. She is working within a tight timeframe. Stuck in Montreal for much of 2020, she lost a year where she could have done archival research in India on the history of women and theatre in South Asia. She has had to extend her program. But there are no guarantees that McGill’s History department will extend her scholarship beyond the fourth year of her research.

“After my fourth year, my funding expires…I have a year and a half left to submit my thesis.” Singh hopes that her university will decide to extend funding for international PhD researchers.

Emotional struggles

Rigorous academic expectations can be another major stressor. Regino has struggled with depression in the past. Despite sometimes being overwhelmed by his studies, he could not drop out of courses. International students need to maintain a full-time course load to remain in good standing in the eyes of immigration authorities.

The UÉQ has raised alarm over the mental health crisis affecting students and university staff throughout the pandemic. Marcil stresses the links between financial stress and psychological health and believes an emergency fund for mental health services should be made more accessible to international students.

“We need to better train teaching staff…and alert them to the realities of international students for whom there is not a lot of flexibility,” the UÉQ president adds.

For students studying overseas, another factor often weighs on their mind: being thousands of miles away from family. That, on top of pandemic-related restrictions, can lead to even more isolation. Still, Singh and Regino are aware that they are in a better place than many others in their home countries.

________________________________________________________________

This story has been produced under NCM’s Advanced Mentoring program led by Professor Susan Harada and Judy Trinh.

Having worked for a couple of years in the non-profit sector in Manila,

Christopher has written about aid and international development, human rights, immigration and armed conflict in diverse contexts. He is a member of the NCM-CAJ Collective and works as a freelance journalist.