Racially motivated name-calling. Driven headfirst into a desk. Beaten with a switch.

Being part of a minority in Fredericton during the 1970s and ‘80s was a personal nightmare for Rajeev Venugopal.

“I grew up in a constant state of fear of being beaten up for being a “paki,” Venugopal told New Canadian Media. “Sometimes I could fend off an attack, other times I could talk or run my way out of confrontations, but getting beaten up was a regular part of growing up.”

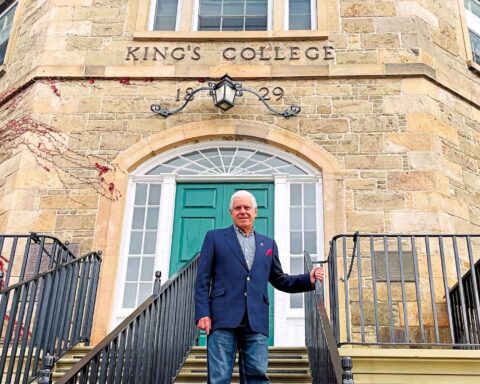

Venugopal, who went on to work in government, academia, policy and international relations, now lives in Ottawa and serves as General Manager of International Relations at Canada Post Corporation and as Canada’s Head of Delegation to the Universal Postal Union (a specialized agency of the United Nations).

Venugopal said while New Brunswick specifically and Canada in general is now more tolerant when it comes to multiculturalism and diversity, that wasn’t the case when he was a youth.

Being a part of a visible minority resulted in him being seen by others in a way that made him vulnerable to both verbal and even physical assault.

“I was beaten up quite badly in the basement of Fredericton churches, in which I would participate in community leadership groups, and received a lashing with a switch in the woods at my school bus stop only 100 meters from my childhood home,” Venugopal said.

“One time I was thrown headfirst into a teacher’s desk and was concussed so badly I couldn’t remember my mother’s work phone number so she could take me to the (hospital) for stitches.”

Most of the time these confrontations were overtly racially motivated, he said.

“In addition to the physical confrontations, I was keenly aware of a certain element in Fredericton that did not take kindly to ‘outsiders.’ This pained me, as I was born and raised in New Brunswick and knew no other home than the one I had in Southwood Park.”

‘Violence, fear, and hiding’

For at least a decade, Venugopal said it felt like each day of his existence was being played out in William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies,” a novel in which a group of stranded schoolboys attempt to govern themselves with horrific, violent outcomes.

“My childhood, therefore, ranged from idyllic afternoons spent deep in reading great adventure classics such as Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, Jules Verne novels and the like, to periods of incredible violence, fear, and hiding.

“To say growing up was difficult would be an understatement, but I also realize that my experience is not necessarily the experience of other racial minority kids who were growing up in Fredericton during the 1970s and 1980s.”

Venugopal, like scores of other New Brunswick residents, made his way through the province’s education system by attending well-known Fredericton schools such as Forest Hill Elementary, the now-defunct Albert Street Middle School and Fredericton High School.

“I did not particularly enjoy grade school and did not fit in well with my peers,” Venugopal said. “My ability to integrate socially was limited at best, and painful at worst, so I buried myself deeply into reading, studies, and a deep curiosity with politics.”

In an effort to defend and protect himself Venugopal, while in high school, enrolled in karate classes on the campus of the University of New Brunswick.

“I was tired of being afraid and made the decision to immerse myself in combat sports,” said Venugopal, who now holds a third-degree black belt in judo.

“I had no confidence in teachers and other community leaders and authorities to give one iota to protect me from harm and realized that I had to be able to be free of fear, be able to control my emotions and learn how to fight properly.

“Since those early days, I have been actively involved in martial arts for some 35 years now, and participate in these activities more for fitness, fun, self discipline, and character development.”

Data for equity

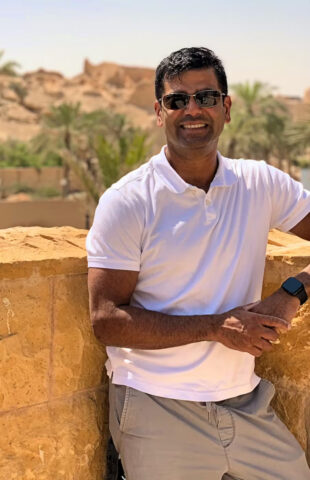

Statistics Canada Chief Statistician Anil Arora said efforts are currently being made to understand the strengths, requirements and well-being of different community groups, whether from India or some other place in the world, through data analysis.

Arora said the Disaggregated Data Action Plan, an approach now being led by his organization, helps uncover hidden trends in society and assists in identifying and revealing challenges experienced by vulnerable populations, such as racial and ethnic minorities.

By highlighting their experiences to better reflect their ordeals, voices are being heard, Arora said.

“In an environment where we have no real capacity for talent to be wasted — and resources are always precious — we want to make sure everyone has an equitable chance of success,” Arora said. “Statistics don’t solve the problem by themselves but as you start to disaggregate that data, they start to put questions on the table about why (certain things are happening).”

Arora, also of Indian descent, said the action plan gives analysts a sense of where to dig into to try and solve any inequities that may exist.

“The data, themselves, is not the answer but they are a key piece in trying to get to the answers if one listens to what the data are saying.”

Fight back against racism tax

Venugopal, meanwhile, said his father, D.V. Venugopal, a geologist, and mother, Shantha Venugopal, a chemical technologist, were part of the first waves of South Asians to settle in New Brunswick.

“My parents’ generation of Indian immigrants to New Brunswick and more broadly Canada faced tremendous barriers to inclusion to Canadian society, often feeling highly marginalized and stigmatized,” Venugopal said. “In a way, I think that my parents’ generation faced racism in their community as the price they needed to pay in order to come to Canada.”

It was like a tax, Venugopal said.

“I think that the reason we did not see as much activism in the community during the first wave of Indian immigrants that came in the 1950s and 60s, was because they realized that paying that tax was the price to assure the children’s future in a free Canada,” Venugopal said. “Not just Indians, but all of them. All the coloured ones. Where the narrative changed was when their children had the audacity to believe that they were equal and revolted against paying the tax anymore. They did not just hope for a better life, they laid a claim to it.”

“Where the narrative changed was when their children had the audacity to believe that they were equal and revolted against paying the tax anymore. They did not just hope for a better life, they laid a claim to it.”

— Rajeev Venugopal

A vocal proponent for gender equality, sexual/gender orientation, racial equality and refugees rights, Venugopal said the unpleasant challenges experienced in those early years helped set the stage for him to concentrate on fighting bigotry and hate in all of its forms.

In his junior and senior high school years, Venugopal became involved in activities with various multicultural associations and organizations, where the underlying goal was to promote the community’s diverse ethnocultural fabric as a strength rather than an impediment.

“Later on, I decided to study political science after learning about the horrors of the Holocaust during one particular history class,” Venugopal said. “As I learned more about societal conflict, I gained a deep appreciation for the importance of an informed citizenry in which the principles of morality and justice for all were ingrained in the machinery of government.”

As a professor at UNB and St. Thomas University, Venugopal based the courses he taught around educating students on the principles of governance and policy development, with the concept of a “just society” at the heart of his lesson plan and pedagogy.

Indian identity

Over the years, Venugopal said he aspired to several career directions, including serving in Parliament, financial markets, advancing in the public service, and/or joining the foreign service.

“I had never thought about joining the national postal service as a career move, let alone having Canada Post’s international business team being the nexus in which all of these interests and aspirations would converge into a single point.”

In the meantime, Venugopal said he has successfully challenged his own biases about his identity and his place in society.

“I started to travel to India regularly for work over 15 years ago, and discovered the new India that was powered by innovation, traditionalism, and modernity. In my head, I was able to square my identity as a Canadian of Indian origin, which allowed me to see the strength of India, Indians, and Indians in Canada, such as my parents.”

Despite those early barriers, statistics show that Canada has now become the place to be for people of Indian descent.

As reported by New Canadian Media in November, India produced the highest number of people who became new Canadians in 2022. In all, 59,503 Indian-born nationals took up Canadian citizenship, a 171 per-cent increase from the previous year. Altogether, Indian nationals represented 16 per cent of the 375, 413 people who became Canadian citizens in 2022.

“Having been to many countries and regions around the world, I believe Canada offers a place to live in peace, with space, and generally a high standard and quality of living,” Venugopal said. “Like all people, Indians value having a clean and stable environment in which to raise children and live in peace. This is, I believe, a major factor to the growth of the Indian population in Canada.”

Arora said the proportion of South Asian migrants born in India is expected to continue to grow in the coming years because of the skill sets currently needed in Canada and the interest in that part of the world by people who want to make a future in this country.

“An outcome of that dedication and commitment is a Canada that has the labour market that it needs, the skills that it demands, and counters some of the demographic changes that are prominent in this country,” Arora said, pointing to an ageing population with more seniors than children.

Like most immigrants coming to Canada, those of Indian origin have an intrinsic desire to succeed and leave a legacy for their children, Arora said.

“There are some motivations there to make sure they can earn a good living, put some roots down, make sure their kids are educated and essentially kind of participate in the Canadian dream.”

Story and photos were produced in partnership between New Canadian Media and Saltwire.

Michael Staples

Michael Staples is a retired daily newspaper reporter from New Brunswick with more than 30 years experience. He has travelled extensively with Canada’s military and has reported from Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and Macedonia during the Balkans War and from Haiti in 2004 following a three-week bloody rebellion that saw then-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide flee the country. He has also written extensively about Canada's involvement in the Afghanistan War. Michael has considerable experience covering crime, justice and immigration issues. In 1999 he was the lead journalist reporting on the airlift of hundreds of refugees from Kosovo to Canadian Forces Base Gagetown. He has been nominated twice for Atlantic Journalism Awards.