An editor’s open letter following her firing by a Chinese-language newspaper over the Michael Chan affair has re-opened the conversation among “ethnic” journalists about professional standards and the future of the industry.

An editor’s open letter following her firing by a Chinese-language newspaper over the Michael Chan affair has re-opened the conversation among “ethnic” journalists about professional standards and the future of the industry.

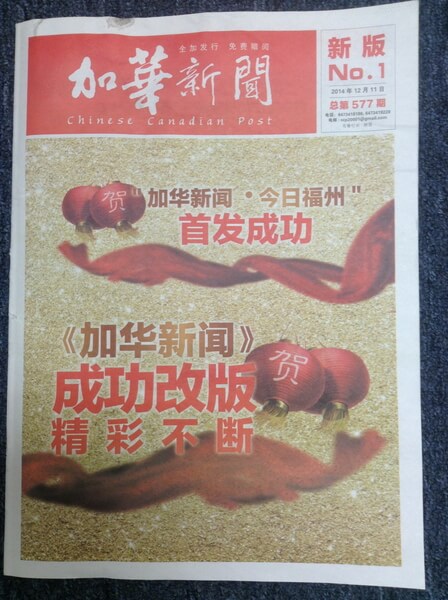

In her open letter to the Chinese media, Helen Wang, the former editor-in-chief of the Chinese Canadian Post (pictured left), claims she was fired because she published an article written by columnist Jonathan Fon criticizing Michael Chan.

“Not to mention the legitimacy of Jonathan Fon’s column, the fact [Wang] was fired without any reasoning indicates further evaluation is needed on Chinese media employees’ tough work environment,” Wang writes at the start of the open letter.

The letter continues by arguing that media, as a “social conscience,” should be separated from any government influence and reveal truth. However, the hardship of making a living working in the Chinese media is hard to ignore – some newspaper’s publishers sacrifice their journalistic standards in return for more advertising revenue.

“What I don’t like the most is that my story was always compromised by heavy workload. I tried to be unbiased but at the end of the day, we don’t have enough resources or manpower to do a balanced story.” – Min Li, former journalist

Wang concludes by expressing her lifelong passion in working as a journalist, and promised to return to Chinese media in the future. Jonathan Fon, on the other hand, assured he would keep freelancing and speak out without being influenced.

Journalists struggle under pressures

Min Li, who used to work at a daily Chinese newspaper based in Scarborough, didn’t hesitate to speak about her frustration working as a reporter for seven years.

“What I don’t like the most is that my story was always compromised by heavy workload. I tried to be unbiased but at the end of the day, we don’t have enough resources or manpower to do a balanced story. It’s not about quality that we are working on. It’s the quantity the editor targets.”

Li adds: “The workload is fixed with two stories a day, at least 800 Chinese characters per story. Nobody cares how thorough or how balanced your story is as long as you submit two stories at the end of the day.”

Several months ago, Li quit the job and became a freelance interpreter. Without a stable bi-weekly paycheque or any medical benefits, she is determined to go in a new direction and build up a professional career she firmly believes in.

What cost Wang her job at the Chinese Canadian Post was an article Jonathan Fon wrote right after the Globe and Mail published a two-day investigative feature on Ontario cabinet minister Michael Chan’s ties with the Chinese government and the fact he was investigated by CSIS, Canada’s spy agency.

Li is lucky to be young and single. Jianxin Huang, on the other hand, is a father to two teenage children. He worked as an editor at a newspaper that no longer runs in the community, losing his job after three years.

Huang graduated from university in China with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. Between his work experience in China and here after immigrating to Canada, he had been in the newsroom for two decades.

Huang had to enlist the help of Second Career, a program funded by the Ontario government that provides laid-off workers with skills training and helps them find jobs in high-demand occupations.

“I now work as a construction worker, going everywhere in the GTA. It’s very different than the job I had been doing for decades in newsroom, but I’m happy with what I got,” Huang says. Although his workload is quite literally heavier, he admits he earns a higher wage and gets more comprehensive medical and dental benefits, as well as work injury insurance.

What cost Wang her job at the Chinese Canadian Post was an article Jonathan Fon wrote right after the Globe and Mail published a two-day investigative feature on Ontario cabinet minister Michael Chan’s ties with the Chinese government and the fact he was investigated by CSIS, Canada’s spy agency.

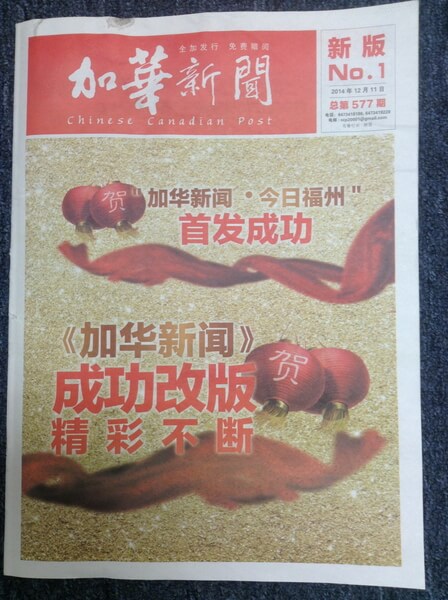

Fon argued in his column (pictured right) that Chan doesn’t represent the Chinese community, only his constituents. CSIS’s investigation on Chan is about his own integrity and has nothing to do with the Chinese community.

Fon argued in his column (pictured right) that Chan doesn’t represent the Chinese community, only his constituents. CSIS’s investigation on Chan is about his own integrity and has nothing to do with the Chinese community.

Chan’s office has denied any involvement in Wang’s job termination.

Chan files lawsuit

In the meantime, Chan has already filed a libel suit with the Ontario Superior Court of Justice against the Globe and Mail for its two features that suggested his ties to the Chinese government. In the statement of claim, he seeks $4.55 million in general and punitive damages.

“This has been a difficult time for me and my family … Since these stories were published, I have given a great deal of thought to the impact the unfounded allegations against me will have in the immigrant communities of Canada,” the claim says.

In the claim, Chan also indicated that his personal goal “in this litigation is to clear my name and restore my reputation.” He will donate any amount awarded to him by the court to PEN Canada, a writers’ association for freedom of expression, and the Markham Stouffville Hospital Foundation.

During an interview with Sing Tao Daily, one of the largest Chinese daily newspapers in North America, Chan indicated that he has met with Ontario’s Integrity Commissioner, asking about who pays for his libel-suit fees given the triple identities he has as an MPP, a cabinet minister and a citizen. He said it would take the Integrity Commissioner one month to give a proper guideline.

Shan is a photojournalist and event photographer based in Toronto with more than a decade of experience. From Beijing Olympic Games to The Dalai Lama in Exile, she has covered a wide range of editorial assignments.