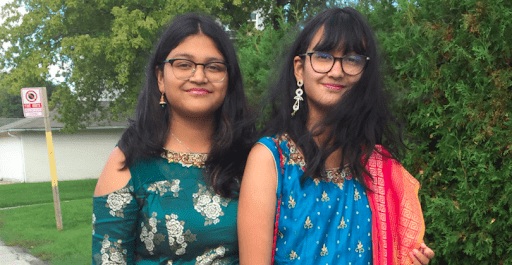

Abha Ghosh, who moved with her family to Toronto from India in 2012, enrolled her younger daughter, Shayantika, in a French immersion school when she was six, while her older daughter, Nayanika, attends an Anglophone school. At home, the family speaks Bengali and English.

Despite having no knowledge of French, Abha believes that by enrolling her child in a French immersion school, she is giving her an edge in life.

“Children are used to learning many languages at a very young age,” she explains about her decision.

Abha’s not alone in thinking this.

While many non-French speaking people immigrate to Canada each year, the demand for French immersion schooling has been growing, as parents hope to give their children more opportunities in life.

According to research published by Canadian Parents for French, in just four years, between the 2011-’12 to 2015-’16 academic years, there was an increase of nearly 20 per cent of students enrolled in French immersion programs, from around 360,000 to 430,000 students.

Struggles with enrollment

However, despite the demand for French immersion in Ontario being higher than the supply, “access to Francophone schools is too dependent on the lottery system,” explains Abha about the struggles parents face with enrollment.

Based on applications received during the first Phase, all grade one French immersion classes are created through a lottery system that is either digitally randomized or selected based on eligible applications.

This means that students with a sibling in a French immersion school have a higher chance of securing a spot, while at the “bottom” of the waiting list, following a long set of criteria, are students residing beyond the school’s vicinity.

Even so, unlike her sister, Nayanika was unable to secure a spot in a French immersion school due to limited spots and an overwhelming number of applications.

Additionally, despite the high demand for knowing French as part of many job application requirements, bilingual applicants are limited because the number of Francophone classrooms has increased only slightly, which in turn has left parents grappling with enrollment and transportation challenges as well.

But this hasn’t deterred newcomers who continue actively working to ensure their children get a spot in French immersion schools.

According to the study from Canadian Parents for French cited above, in Ontario, registration for French immersion programs has been increasing consistently for almost 15 years, at an average rate of five per cent per year. It should be noted that French immersion programs in Ontario have been optional since their inception in the 1960s.

Nasrin Akhter Jahan, a Bangladeshi mother of three, also wanted to enroll her daughters in a French immersion school to ensure her children know both the official languages, which “might help them in their career.”

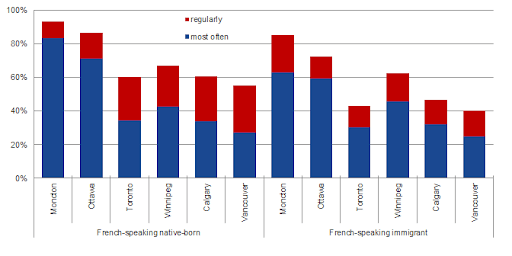

“It is crucial to think about the children’s future,” she says, adding that Canada offers many opportunities to skilled immigrants who are proficient in both English and French, especially in government jobs.

This is a strategy employed by many newcomer parents.

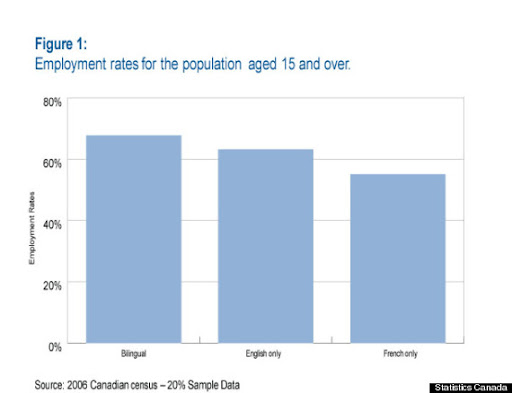

A new analysis of Canada’s 2016 census reports that those who know and use both of Canada’s official languages at work earn more than their unilingual counterparts.

Accordingly, a study released in 2019 by the Office of the Commissioner of Officials Languages, corroborates that many parents believe this decision will give their children more educational and professional opportunities.

Outweighing challenges

Abha says it’s often a struggle for non-French speaking parents to help their kids with their homework, which is why it’s often the siblings who help each other learn the new language.

For example, Shayantika, who is in grade seven and relatively fluent in French, sometimes helps Nayanika, in grade nine, with her French homework.

And “when the pandemic restricted children to online learning from home,” Abha says, “the teachers were very supportive.”

Nasrin agrees, saying she believes teachers are aware that non-French-speaking parents struggle to help their children with homework, which is what makes them so crucial.

Despite that, in 2020, the Ontario Government acknowledged that there are not enough French-language teachers in the province.

To address this, the government has recently committed to investing in a $62 million Francophone teacher recruitment and retention strategy as part of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023.

But is it enough to meet the rising demands of interested parents who are keen to admit their children to French schools?

Nasrin has two daughters and a son: the younger two attend a French immersion school while the oldest sister, Nayeema, completed her middle school education at an extended French school, a program that begins in grade seven and provides another way for students to learn the language by offering some subjects in French.

While Nayeema initially experienced challenges in learning subjects like science and geography in French, the program helped her to eventually develop a solid grasp of the language.

“Deciding against the flow is always hard,” says Nasrin, referring to the many immigrant parents who do not have a French background and therefore choose to not enroll their children in French immersion schools, fearing they won’t be able to help them.

But from both Abha’s and Nasrin’s experiences, they are sure that the benefits of French immersion programs are numerous for their children’s future and outweigh any challenges.

This story has been produced under NCM’s mentoring program. Mentor: Joyeeta Ray

Giada Ferrucci is a Ph.D. student in Media Studies at Western University. She holds a BA in Economic Development and International Cooperation from the University of Florence, Italy, and an MA in International Relations from Aarhus University in Denmark. Her doctoral research focuses on the intersection of environmental justice and social movements.