Although cultural diversity seems to be widely promoted among Canadian universities, diversity within classrooms is limited by the need to conform to a monolingual reality.

Dr. Andrew McGillivray, assistant professor in the department of rhetoric, writing, and communications at the University of Winnipeg, faces the challenge of how to integrate rather than assimilate students in their written academic expression. He says the curriculum might be intercultural, but the monolingual expression required is “unavoidable” in an environment where English is the dominant language and students are expected to be proficient in institutional academic standards.

In McGillivray’s intercultural communication class, students are able to connect to their heritage by translating text in a language other than English. The concluding text, however, is in English.

“This contradiction, which results in a conformity to Anglo standards, is necessary for the intended reader,” McGillivray said during the second day of the 4th annual Metropolis conference, which this year touched on themes of inclusivity, diversity and anti-racism within the context of Canada’s 50 years of official multicultural policy.

“The instructor is only expected to be proficient in English.”

Monolingual bias in technology

“Bias in favour of English is largely unseen but baked into both the hardware and software used globally and used in our classrooms,” said Dr. Jaqueline McLeod Rogers, department chair of rhetoric, writing, and communications.

She pointed to the recently released book, Your Computer is on Fire, that probes who technology is serving and what is being valued.

The book gives the example of the “QWERTY” keyboard as privileging those who use Latin based alphabets. This limits the range of expression available to speakers of other languages. Even though it fails to accommodate languages used by over 50 per cent of the world’s population, this model remains dominant.

In her work titled “Algorithms of Oppression,” Safiya Umoja Noble also demonstrates how search engines reproduce cultural biases and stereotypes. For example, her Google search of “black girl” back in 2010 brought up mainly pornographic images. These biases reflect the views of largely white, male Silicon Valley programmers.

McLeod Rogers said that according to Noble, programming is often done through the lens of “white equals good,” which means “your robot’s brain is running on dirty data.”

The issue is that such homogenous data which doesn’t account for the diversity of human thinking is being used to make critical decisions, said Rogers, “such as who’s guilty or innocent if we’re in the legal framework. In education, who gains admission or who might be denied, who would receive funding or tuition adjustments.”

In Whose Global Village?: Rethinking How Technology Shapes Our World, Ramesh Srinivasan argues that if technology shapes our world, we need to widen the circle of creators and develop a framework sensitive to local rhythms. Rogers said Srinivasan emphasizes the need for a “planetary framework” that mobilizes local communities to develop technologies that fit their needs, as well as providing opportunities for global connection and collaboration.

Creating space for alternative expression

There is a difference between a culturally diverse class and an ethno-sensitive one, said Helen Lepp Friesen, another instructor in the department of rhetoric, writing, and communications. The latter requires an intentional focus.

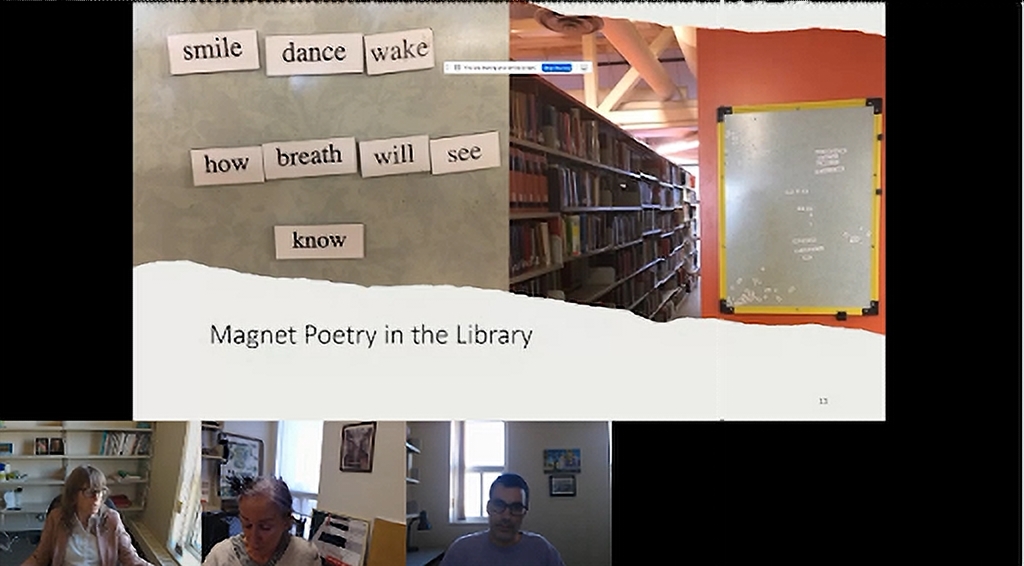

An important part of Lepp Friesen’s strategies to honour students’ diversity within her classroom is creating a “relaxing and encouraging environment.” She uses games that motivate students to fully participate and enjoy their learning at the same time and encourages demonstration of knowledge in unconventional ways, including other talents such as music.

Spaces outside the classroom also provide fertile ground for learning opportunities, such as contributing to the nearby Spence Neighborhood Association’s public writing art piece with sidewalk chalk.

In Lepp Friesen’s view, “writing comes alive when it serves a purpose. If students can buy into the purpose, they will take more genuine ownership of their writing.”

These kinds of intentional strategies by instructors to honour cultural diversity are needed to ensure that students feel truly welcome within their classrooms.

As Lepp Friesen said about multiculturalism, “after hundreds and hundreds of years of doing exactly the opposite, making a public declaration doesn’t suddenly make living and working in a global culture harmonious.”

Daniela Cohen is a freelance journalist and writer of South African origin currently based in Vancouver, B.C. Her work has been published in the Canadian Immigrant, The/La Source Newspaper, the African blog, ZEKE magazine, eJewish Philanthropy, and Living Hyphen. Daniela's particular areas of interest are migration, justice, equity, diversity and inclusion. She is also the co-founder of Identity Pages, a youth writing mentorship program.