When Montgomery Gisborne dropped off his wife and 8-year-old daughter at the Vancouver International Airport 10 days ago, he didn’t know they were boarding a plane that would be flying right towards ground zero of the deadly coronavirus outbreak.

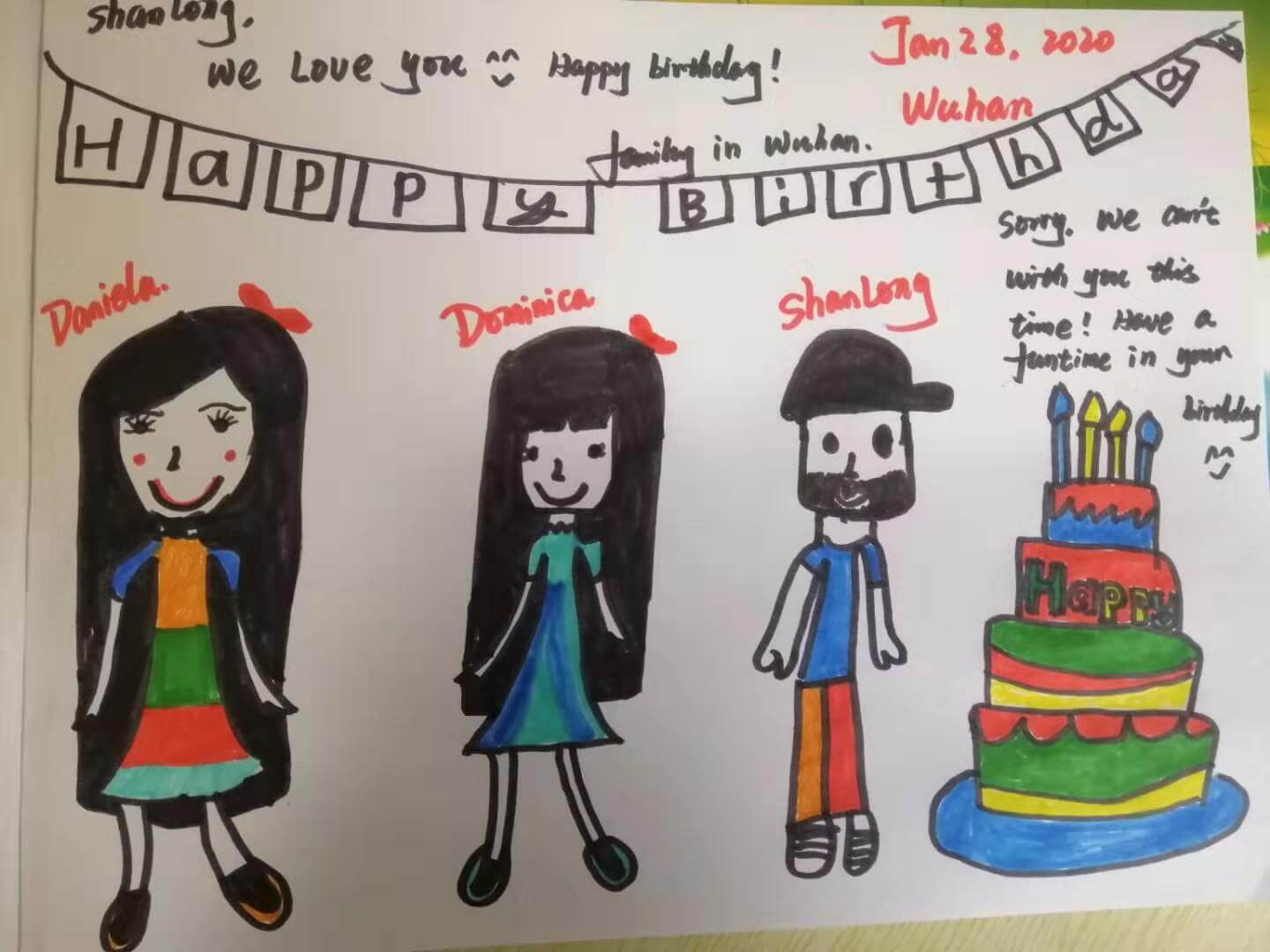

Gisborne’s wife, Daniela Luo, had planned to visit her parents and celebrate the Lunar New Year in her hometown of Wuhan, China. Luo had not seen her parents in five years. Gisborne had just started a new job and couldn’t go, but Luo and daughter, Dominica, went ahead with the scheduled trip to Central China.

When they left Jan. 17, there were no travel restrictions in place, no global health alerts.

“Take care of yourself and our daughter,” Gisborne recalls telling Luo, as he hugged them. “I’ll be waiting for you to come back soon my girls.”

Now with Wuhan in lockdown, and travel bans expanding as the number of people infected with the coronavirus grows, Gisborne is growing increasingly anxious. He checks the infection numbers daily and tracks the rising death toll. His mind is preoccupied with getting his family out of China.

“I want to not only get my wife and daughter back, but also my wife’s parents,” Gisborne said. “But how?”

The number of people infected by the respiratory illness has already surged past 4,500 and claimed more than 100 lives (as of the morning of Jan. 28), according to the National Health Commission. The overwhelming majority of people affected are in central China. Wuhan’s mayor has acknowledged that the city may have 1,000 more cases, and work is underway to build a temporary hospital on the outskirts of the city to treat infected patients. As of Jan. 28, there are more than 70 confirmed cases in 17 places outside of China, including at least five in the U.S.

On Monday, Canadian health officials announced that there was a second case of presumptive new coronavirus in Toronto.

Low-risk trip turned to high-alert in one day

Before Luo left Canada, Chinese authorities had said there was no need to worry, that the coronavirus was under control. But one day after Luo and her daughter landed in China, Wuhan went into a state of emergency.

On Jan. 20, Luo received an overwhelming amount of news and messages on her cellphone. All were about one topic: the coronavirus. The virus was spreading throughout the city and the surrounding province. Luo was shaken after she received a phone call from a cousin who works in a public health office.

“He told me to leave Wuhan as soon as possible,” said Luo. Then her husband contacted her through the Chinese messaging app WeChat and urged her to fly back to Canada. But Luo wanted to stay to care for her parents.

“How can I leave my parents alone in such a severe situation? I love them so much. I will be worrying about them if I leave.”

But Gisborne pushed back.

“I understand she loves her mom and dad, but I also love my wife and daughter. I’m worrying about them,” said Gisborne.

Finally the couple reached a compromise and decided to shorten the planned month-long trip to 10 days and booked a return flight to Vancouver.

But they wouldn’t get out. On Jan. 23, Chinese authorities halted public transportation and stopped all flights and trains in and out of Wuhan, effectively putting the city of 11 million people in lockdown.

Even as more cases are detected in more countries, Luo, who is in the eye of the storm, says residents are remarkably calm. She lives in Hankou district, just 10 kilometres from Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the health officials believe the coronavirus was first transmitted from animals to humans.

“Streets are empty and passerbys wear masks. But no high prices, no lack of food.” Daily necessities can still be purchased in supermarkets or groceries and Luo’s parents are trying to live life as normally as possible.

“My Dad still goes to the farmers market every two days,” said Luo. But she chooses to stay in the house with her mother and daughter.

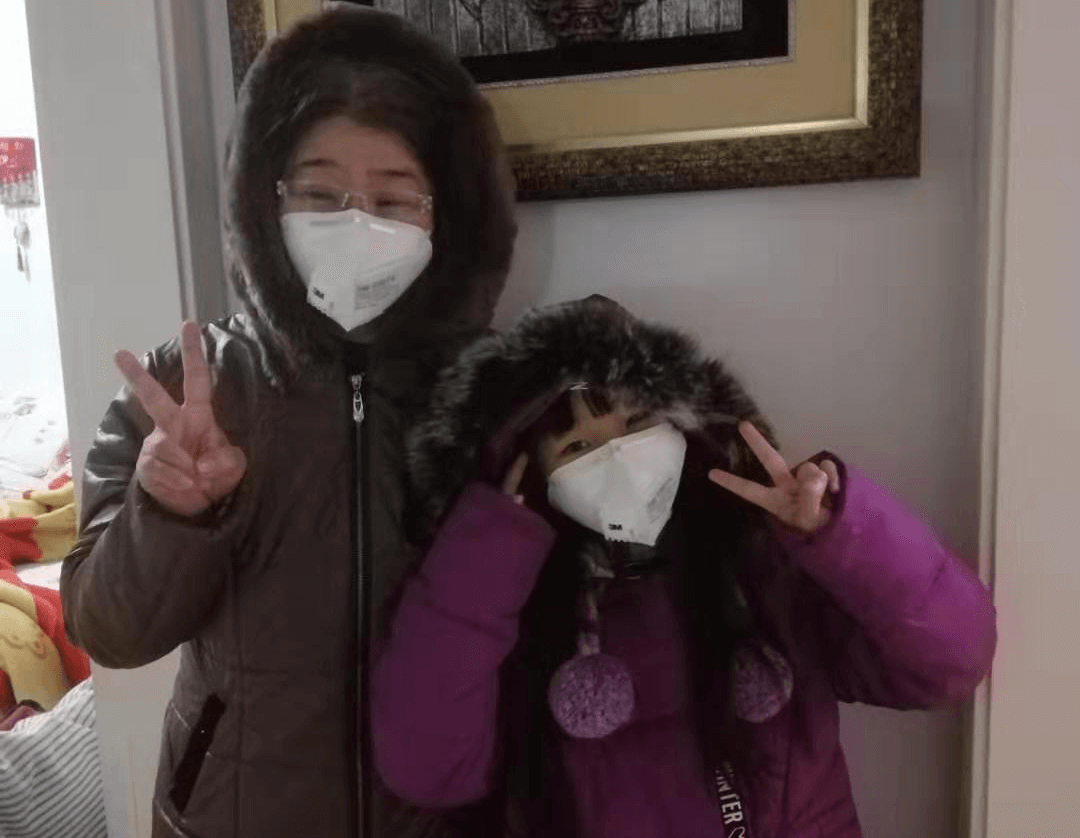

There are growing concerns. Too many patients, not enough doctors. Chinese social media is full of news reports about doctors who can’t get protective clothing and shortages of medical supplies. Also, pharmacies are running out of medical masks and disinfectant. Luckily, Luo’s friends gave her family two boxes of 48 face masks.

No evacuation plans for Canadians

Global Affairs Canada says it is working closely with the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada to provide guidance to our diplomats serving abroad and their families. There are approximately 67 Canadians in Hubei province, where the city of Wuhan is located, but officials say this may not be a complete picture of the number of Canadians in the region or China. Global Affairs is recommending against traveling to Hubei, but unlike other countries, the Canadian government has not arranged plans to evacuate its citizens from the area. It has offered consular assistance.

The U.S. government has plans to charter flight to evacuate American citizens and diplomats from Wuhan. Diplomats from other countries, such as South Korea and the United Kingdom, are also arranging their own transportation out of Wuhan.

‘Wuhan people will never give up’

Luo is trying to remain optimistic. She cannot visit her friends and relatives, but she is keeping in touch through WeChat or by phone. She’s also grateful her daughter gets to spend more time with her grandparents. Luo spends her day teaching her daughter Mandarin and math, or watching television with her parents. She says she has confidence that the Chinese authorities will be able to contain the virus soon.

“This is a hard-fought battle, yet I believe we will win. I was born in Wuhan and I know Wuhan people never give up. We will be fine.”

This story has been produced under NCM’s mentoring program. Mentor: Judy Trinh.

Jessie Zheng is a freelance writer and documentary director based on Prince Edward Island. She is a member of the NCM Collective.