Taiko drums vibrate through the trees across Oppenheimer Park in Vancouver, B.C. The older generations relax in the seniors’ tent as young ones in blue and pink kimonos toddle in front of the stage. Some of them hold colourful striped balloons hanging down from strings.

The 39th Annual Powell Street Festival celebrating Japanese Canadian culture, traditions and identity is underway with entertainment, costumes and music. It has also returned to its usual location.

“Last year the festival had to temporarily relocate when many of the city’s homeless set up a tent city at the park to protest against Vancouver’s social housing solution.”

Last year the festival had to temporarily relocate when many of the city’s homeless set up a tent city at the park to protest against Vancouver’s social housing solution: gentrification and ‘renovictions’ in the downtown eastside. Oppenheimer Park, located in the centre of the city’s Japantown, was one of many internment camps during World War II when Canada declared war on Japan.

Some of this year’s festival highlights include a talk from well-known environmental activist David Suzuki about his book Letters to My Grandchildren and for the foodies, a modern interpretation of the ever-so-popular SPAM musubi from Hawaii. Yes – it’s a slice of fried SPAM meat on rice, secured with a strip of dried seaweed called nori.

A closer look at the art of kyudo

The festival’s barbecue salmon booth, which sells this option, even offers a SPAM musubi kit – a can of SPAM, a SPAM sushi press, soy sauce, rice and nori. While a sumo competition is being set up in the middle of the park, Mike Nakatsu (pictured right) is shooting arrows at the nearby Vancouver Japanese Language School, where part of the festival is held indoors. The kyudo demo is over, but practitioners remain.

Kyudo means “way of the bow” and is described as the Japanese martial arts of archery. Historically, archery was used for war or hunting, explains Nakatsu. “Every single culture had the bow and arrow. With the use of gun powder, it died off.” The Vancouver Kyudo Club founder says the modern practice is for spiritual, moral and social development. “I get to meet people all over the world because of kyudo.”

When it comes to spiritual development, whatever you put into it is what you get out of it, he explains. Moral development, he adds, creates discipline and also requires discipline.

“From a practical point, you want to hit the target. But if you’re so focused on hitting the target that you forget everything else, you’re gonna miss the target.”

Vancouver Kyudo Club founder, Mike Nakatsu, says kyudo is a metaphor for life. Kyudo is also commonly seen in an annual memorial ceremony in Japan during the Coming Of Age Day.

Nakatsu says kyudo is a metaphor for life.

“First, you’ve got to fix what’s here – your stance, your psychological mindset – before you can even care what’s going on [with the target]. You’ve got problems in your life, right? You can’t fix what’s out there, but you can fix what’s in you. So if you fix what’s in you, usually what’s out there fixes itself.”

Thunk! Thunk! Arrows fly into the bull’s eye targets as Nakatsu emphasizes his point.

“If you have good stance, good form, good mindset, you should hit the target. If you don’t, there’s nothing you can do out there except come back, redo your stance and change your mindset.”

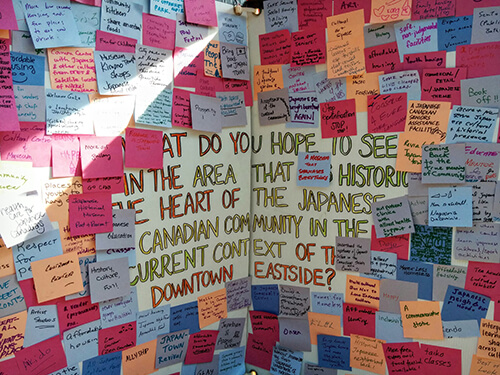

Attendees were asked, “What do you hope to see in the area that was historically the heart of the Japanese Canadian community in the current context of the downtown eastside?”

Nakatsu says competition judges look for the tatesen, the cross in the body with one vertical line of the shoulders and arms and one horizontal line with the head and spine. He says they’ll also look at the breathing, mezukai, which are the eyes, the gaze, fluidity of movement and leading of the hips when shooting.

“There’s also working of the spirits,” he adds. “It sounds rather general but when an [eighth-degree black belt kyudo practitioner] does it, you can feel it. You can feel the presence.”

Nakatsu says kyudo has made him a better person in society.

“If you can have complete control and composure when someone is kicking you in the head, you can probably do it throughout your life,” he shares.

Reviving Japantown

Back on the streets, crowds of families with their dogs remain lined up in front of smoking food booths. As supplies dwindle, more items are crossed off the menu. One booth ends up with only black sesame ice cream left for people with a sweet tooth.

Back on the streets, crowds of families with their dogs remain lined up in front of smoking food booths. As supplies dwindle, more items are crossed off the menu. One booth ends up with only black sesame ice cream left for people with a sweet tooth.

The Powell Street Festival Society booth has a board (pictured left) with the question, “What do you hope to see in the area that was historically the heart of the Japanese Canadian community in the current context of the downtown eastside?”

The organization’s office is not located near historical Japantown, but one volunteer says the society wants to move its office to somewhere on Powell Street.

Before doing so though, the organization wants to know what community members are looking for from the space it’ll provide.

Most of the notes with feedback read: “affordable housing”.

Youth space, museum, a Japantown ‘revival’ and traditional food workshops are other popular suggestions.

Deanna Cheng is a freelance journalist who has been published in various publications such as Vancouver Courier and Asian Pacific Post. She often covers culture, intersectionality and Vancouver.