Detainment without trial. Denial of adequate medical care. Overcrowded and dangerous facilities. The Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) has recently been plagued with allegations of inhumane treatment towards people held in immigrant detention.

“Recently we have heard about a lot of scandals in immigrant enforcement and detention, including number of deaths in detention – 11 in the past 10 years,” says Tings Chak, an organizer with No One Is Illegal Toronto (NOII). She mentions that many migrants are held without being charged or having gone on trial. Investigations by Global News into the CBSA also revealed an overall lack of transparency around decisions to arrest, detain or deport migrants.

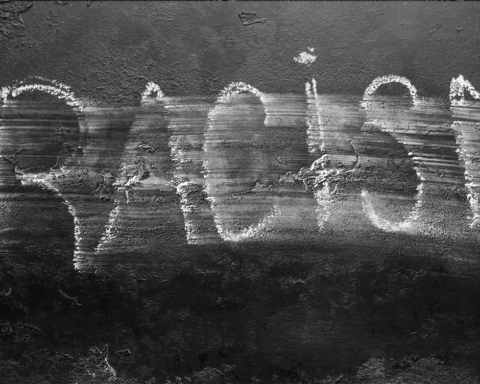

Anger and frustration at these issues culminated in a demonstration organized by No One Is Illegal, this past November at the Toronto Immigration Holding Centre in Rexdale. Various migrant rights groups across the GTA attended.

On a chilly afternoon, the protesters stood outside of the barbed-wire fence surrounding the building. They were holding drums, noisemakers, bullhorns and home-made instruments, in order to create a racket that would attract the building’s occupants: migrants being held in detainment by the CBSA. The demonstration was planned as a show of solidarity to the migrants inside, and to call for an end to the Canadian immigration detention system in which migrants can be held for many years.

“Far too many migrants live and work in precarious and unjust conditions. Many are deprived of their liberty, rather than met with empathy and necessary protection.” – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

The demonstrators’ presence did not go unnoticed. As the group chanted, “No borders, no nations, stop the deportations,” detainees could be seen in the building’s uppermost windows, waving back fervently.

This protest was held just weeks before International Migrants Day on December 18, which was celebrated by more demonstrations in Toronto and around the world in support of migrant rights. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issued a message underscoring the troubling nature of migration. “Far too many migrants live and work in precarious and unjust conditions,” the message read. “Many are deprived of their liberty, rather than met with empathy and necessary protection.”

Ki-moon also called for states to implement the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, of which Canada is not a signatory. His message provided an opportunity to examine Canada’s own system and look closely at how it treats these vulnerable members of society – particularly those in detention – who are often undocumented workers or unsuccessful refugee claimants, some with children who are kept in holding with them.

Lack of transparency

According to a July 2014 report by the End Immigration Detention Network (EIDN), a migrant rights umbrella group, there were 7,373 migrants held in detention holding centres and prisons across Canada last year. Unlike other western nations, Canada has no limit to the amount of time a migrant can be held in detention. Instead, detainees meet with an immigration and refugee board member every 30 days to review their case. Yet many have consistently lost their claims and remain detained for extended periods of time. One of Canada’s longest held migrants, Michael Mvogo, also known as “The Man with No Name”, has been in detention for over seven years.

The EIDN report also revealed significant variations in the rate of migrant release throughout Canada. Release rates were at a low nine per cent in Central Canada, compared to 24 and 27 per cent in the Eastern and Western regions, which raises questions about the consistency of release decisions across the country. Release rate statistics have also shown a significant decline since 2008. However, there has been little explanation on these discrepancies. “It is very clear that there is pressure from above to decrease these release rates,” says Chak. “But we don’t know why that is.”

In an e-mail interview, CBSA senior media spokesperson, Esme Bailey explained that detention is only used as a “last resort” after considering alternatives, such as having migrants report to a CBSA office, limiting them to a certain geographic area, or implementing fees to ensure compliance.

“Canadian immigration laws do not permit arbitrary or indefinite detention,” Bailey wrote. Yet despite a number of “checks and balances” performed by the CBSA to ensure fair treatment of migrants, it is still unclear as to why this system does not place limits on the total length of detainment.

Unsafe detention conditions

The CBSA has also been criticized about its lack of transparency and oversight concerning the living conditions of detainees. The deaths that have been reported by Global News are largely attributed to inadequate health care or monitoring. The Red Cross has also discovered unsafe conditions such as overcrowding, traces of mould and poor mental health care in some facilities.

“Individuals detained in a CBSA-administered immigration holding centre (IHC) have access to a range of health services, including evaluation, treatment and referral services.” – Esme Bailey, CBSA

“Individuals detained in a CBSA-administered immigration holding centre (IHC) have access to a range of health services, including evaluation, treatment and referral services,” Bailey states in the e-mail. These services include access to a physician, nurse and psychologist, and 24-hour emergency care. While the CBSA claims to be improving its facilities, it is unclear what specific steps are being taken to address the above allegations.

Criminalization of migrants

Many of the rules surrounding CBSA arrests and detentions also remain ambiguous. According to the CBSA website, a person can be detained if officers have “reasonable grounds” to suspect them of being “unlikely to appear for an immigration proceeding,” if they are, “a danger to the public,” are “unable to satisfy the officer of their identity,” and finally, if they are deemed an “irregular arrival” by the government.

However, the legal justification behind many arrests has come under question by refugee advocates and lawyers, as investigations have found that many are detained without charge and with little legal support.

Earlier this year, the Ontario government declared it would no longer be allowing the CBSA to join road safety blitzes, during which CBSA officers were making arrests for immigration violations. The decision came after an August 2014 commercial vehicle blitz led to the arrest of 21 undocumented workers. It was reported that CBSA officers asked for identification from passengers, and only subjected visible minorities to questioning.

Harald Bauder, academic director of the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS), says that these types of arrests serve to criminalize the migrant population, putting its members in a challenging position when they come to Canada for work or school. “They are suggesting the person has done something criminal, but often the case is that the person did nothing, and the circumstance renders that person illegal.” He believes that describing migrants as “illegal” only furthers this idea. “I have suggested to subvert that term to “illegalized,” thereby emphasizing that there is a political process behind rendering people illegal.”

Canada’s international reputation

These reports of detention and arrest are indicative of a trend of closed borders and diminishing migrant and refugee rights in Canada, which has not gone unnoticed internationally. The UN has criticized the government’s handling of the migrant judicial process and overuse of detention. Furthermore, John Greyson and Dr. Tarek Loubani, two Canadians who were recently freed from imprisonment in Egypt, have pointed out similarities between their experience and Canada’s migrant detention system. They highlight the government’s hypocrisy in criticizing Egypt’s human rights record, while not addressing Canada’s own violations.

“With the current policies the federal government has initiated, a trend has been going on for two decades now where we are seeing an increasing practice of illegalizing immigrants.” – Harald Bauder, RCIS

Canada’s position on migrants also comes in opposition to increasing openness from its closest international ally. Obama recently announced a plan to offer millions of undocumented immigrants the right to work legally. This comes as part of a larger commitment to fixing America’s “broken” immigration system. Harper has yet to offer comments on Canada’s system. “With the current policies the federal government has initiated, a trend has been going on for two decades now where we are seeing an increasing practice of illegalizing immigrants,” explains Bauder.

Greyson and Loubani are adamant that Canada should fall in line with both the United States and the European Union and implement a 90-day limit, to spare migrants and their families the psychological stress of continuous detention. Chak agrees that for detainees, the most damaging aspect of this system is, “being detained indefinitely, without charge or trial, and never knowing when they’re going to come out.”