Newsroom editors should “think twice” before sending racialized journalists to work alone in predominantly white, rural towns, according to one journalist who says he experienced personal racist attacks for doing his job.

“It’s just not a good idea, especially during COVID, because it can be a lot nastier,” Aaron Hemens, 25, former editor of the Creston Valley Advance (part of the Black Press chain), in British Columbia, told New Canadian Media in an exclusive phone interview.

“I want to share this story because I hope editors learn from this and don’t put a racialized person alone in a rural, small town.”

‘A recipe for disaster’

Between 2013 and 2019, the percentage of immigrants settling in smaller cities and towns outside of Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and Calgary grew by 40 per cent. In 2019, the Federal government also launched the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot to “spread the benefits of economic immigration to smaller communities,” across select communities in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C. Presumably, this would also help increase diversity. Creston, however, is not listed as a participating community.

That’s why Hemens, who is half Filipino, says the decision taken by Andrew Holota, Black Press Media’s editorial director, to send him there as the sole editor and reporter in August 2020 was a “recipe for disaster from the very beginning.”

“I would walk down the street and I would get stares from people,” he says. “It made me very uncomfortable.”

According to the latest census data (2016), there are just over 5,300 residents in Creston, most of whom (4,650) list English and French, the two official languages, as their mother tongue. Only 450 respondents list another non-official language as their mother tongue.

Of those, most are of Indo-European origin. Only five are of Japanese origin, 20 are Chinese, and a handful are of Southeast Asian origin, including 10 from the Philippines.

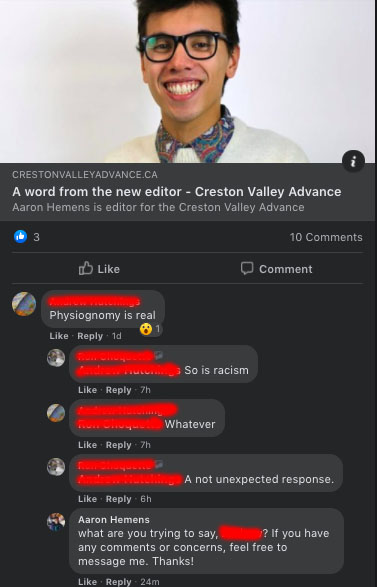

Hemens says he began seeing “red flags” about two weeks after arriving from Ottawa. He says his very first editor’s note saluting the town as a newcomer, which included a picture of himself, was met with derisive comments about his appearance.

“They just made me feel pretty awful. I was scared. I thought, ‘What am I getting myself into here?'”

“Metaphorically lynched”

However, working for one of only two news outlets in town, he felt “compelled” to continue his work.

But things took a dramatic turn after he covered an anti-COVID measures rally on a Saturday in November. Because “a lot of it was false information and dangerous,” he says, he kept his report brief, to around 300 words.

After remotely sending it to Holota, his de facto boss, the piece was trimmed down to just under 200 words and published that same day with the headline: “Creston residents rally against COVID-19 health measures.”

By Monday, “things got weird,” says Hemens, after one of the rally organizers called his office complaining about his report, saying his friends wanted to “metaphorically lynch” him.

“That’s when I knew I should really be careful here,” he says. “I was afraid to go anywhere in public because people knew who I was…It was terrifying.”

“Stop reporting on COVID”

After contacting his boss to let him know of the incident, Holota told him to simply stop reporting on COVID. “That was his solution — just don’t report on it,” Hemens recalls.

For a while, he agreed.

But Hemens says at times he felt compelled to go against Holota’s instructions “when people were crossing the lines” with misinformation.

“I wanted to keep people safe because it’s a small…retirement town,” he says. (The 2016 census shows more than a third (36 per cent) of the population is over 65, and the median age is 57.)

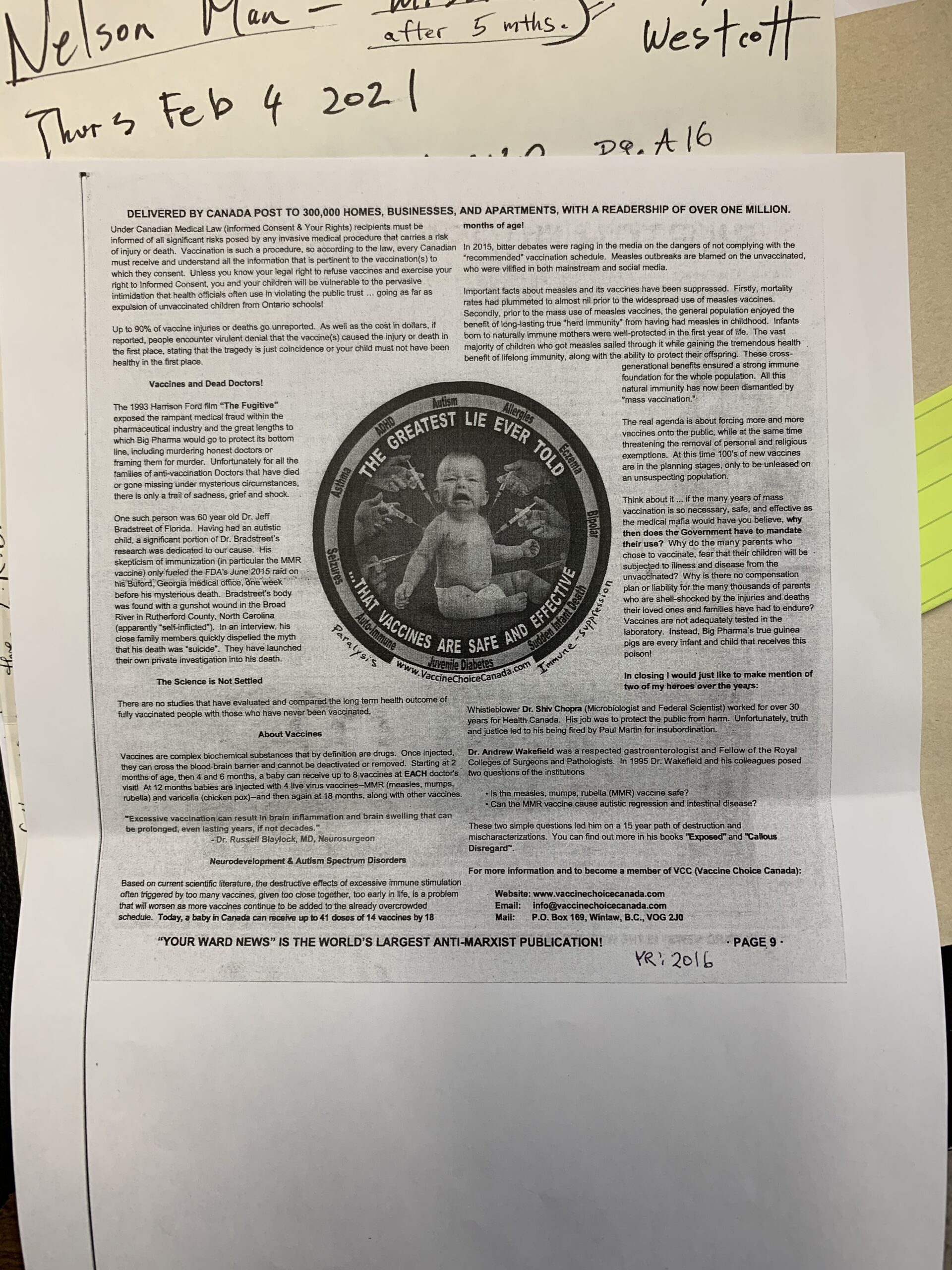

But “that just made matters worse,” Hemens says, with things quickly escalating to the point that he was followed by a car. When he confronted the driver, he was handed a big yellow envelope with his name on it. Inside were a bunch of “conspiracy theories” about COVID and other things, he says.

It didn’t take long for more hateful comments to arrive in his inbox after returning to work from Christmas break in Ottawa in January 2021. That’s when he asked Holota for a transfer.

Three months would go by before he was relocated to Kelowna on April 1, where he worked at the Kelowna Capital News until Dec. 3, when he resigned.

He says his resignation had nothing to do with the incident in question or with Holota but with the need for a “change in pace” from covering breaking news.

‘Censored’

Just before being transferred to Kelowna, however, sometime around March 2021, Hemens decided to take to Twitter to vent his frustration at the racism he had experienced.

He says he tweeted from his personal account and that the tweets had actually begun getting “some traction,” with commenters expressing support for him.

He says this was one of the few ways he could feel connected during this time, as he was “completely alone,” away from friends, family and had little contact with Holota.

But “within minutes,” Holota called Hemens on the phone to ask him to take down his tweets. Hemens says he believes someone must have “tipped off” Holota about the tweets because his response was so swift.

“I was telling him, like, ‘I just want people to know that this is what is happening to me. I want people to know what it’s like to be a racialized journalist in a little rural town,'” Hemens says.

According to him, Holota’s reasoning for asking him to take his tweets down were 1) that “he didn’t want to encourage more (anti-vaccination) behaviour”; and 2) “he was worried that a potential hire would see the tweets and then back out of the job.”

Though he agreed at the time, Hemens now says he felt “censored.”

“That day, I took to Twitter because I wanted to, you know…maybe try to connect (and) have some people understand,” he says. “And the fact (Holota) made me delete them — I just felt shitty. I did it because he was pulling me out of there.”

Hemens said he deleted the tweets before having a chance to take a screenshot of them.

A few days later, on April 1, he was transferred to Kelowna.

Feeling unsupported

Ultimately, Hemens says, he left Black Press “on good terms” and bears no ill will towards Holota, whom he believes was “looking out” for him — but not to the extent that Hemens ever felt safe.

While he recognizes that getting him out meant finding a replacement, which would’ve taken some time, he feels Holota could’ve acted quicker.

“If he really wanted to get me out…he would’ve gotten me out,” he says.

Hemens says he is sure that the fact Holota has probably never experienced discrimination the way he has contributed to how long it took to pull him out.

“I just don’t think he understood how that made me feel, and it just felt so bad,” he says.

Lending credence to that feeling is a recent historic report from the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) that showed that more than half of Canadian newsrooms are led by white people and thus “not representative of the Canadian population.”

“That’s why it’s important to have more BIPOC journalists who can understand what you’re going through and can empathize,” says Hemens.

“Yeah, I left on good terms, but at the same time, I feel like (Holota) never really understood how it affected me.”

The reason for coming forward now, he says, is because he feels it’s important that other BIPOC journalists understand what they’re getting themselves into when being asked to go alone to white, rural Canada, and for editors to realize what they are asking of them.

“A potential hire should know what they’re getting into, was what I was thinking,” he says. “You know — this is what Creston is.”

‘Significant impediments’

Holota declined NCM’s request for an interview.

In an email statement, he wrote that “Black Press Media is committed to a policy of diversity and inclusivity for all its employees.

“All journalists have the right to work in an environment that allows them to feel safe when doing the vital work of chronicling news in their communities and regions. Black Press Media fully supports its journalists in this fundamental principle, and have internal protocols and policies that ensure the safety of all staff.”

He agreed Hemens’ departure was on good terms.

A follow up email pressing him about his rationale for asking Hemens to take down his tweets went unanswered.

Brent Jolly, the president of the CAJ, which represents journalists across the country (though Hemens was not a member at the time of the events in question), says the safety of reporters “both inside and outside of their own newsrooms” is imperative for them to work safely.

Basing his commentary solely on NCM’s description of Hemens’ recollection, and without having spoken to either of the parties in question, Jolly says one of the main takeaways is that “Canada is not necessarily the model for inclusion that we might think or hope we are.”

“I think that really speaks to some of the potentials and the opportunities for racism and pushback when you’re a single reporter working in a town like (Hemens) was,” he said in a phone interview. “There are significant impediments.”

While he hesitates to comment without speaking to the parties, he says “editors need to be aware that the environment journalists are working in is continually changing” and must adapt measures accordingly to keep them safe, including more “mental health supports.”

“These are demands that are increasing, especially in small rural communities,” he says. “There is a role that the news organization has to play in ensuring their staff is protected and trained and insulated to be able to…do their job properly.”

Asked about Holota’s decision to stop reporting on COVID as a solution to Hemens’ harassment, Jolly cautions that, “ultimately, what stories get missed and aren’t told is a reflection of the composition of different newsrooms.”

Legal obligation

Jennifer Moreau, secretary-treasurer of Unifor Local 2000 and a community journalist, says “the employer has a legal obligation to make sure the workplace is free of harassment and discrimination.” Unifor is Canada’s largest private sector union, representing more than 11,000 media workers through its Media Council, which Moreau Chairs.

The Creston Valley Advance is not a union member but Unifor does represent other Black Press Media community papers, mostly in the Lower Mainland.

Regarding the time it took to get Hemens out of Creston, Moreau agrees it would likely take some months, but she stresses that that is only “one of many responses.”

“If it’s online, in the community, out in the field, through letters or emails or social media or phone calls, all of it needs to be monitored and listened to” so that journalists can be protected from harassment, she says.

“It’s not unusual for journalists, especially female and BIPOC journalists, to be targeted. It’s not unusual for them to self-censor because of the harassment they experience from people.”

Last month, an Ipsos survey of online harassment against journalists and media professionals showed that “the issue is pervasive and the attacks are on the rise.”

Balancing act

Again, commenting generally, Moreau validates Hemens’ feelings that Holota’s actions — or lack thereof — may have been driven and clouded by his own background.

“White people tend to play down racism. They don’t understand it the way that BIPOC people do…and they tend to get defensive and minimize it,” Moreau, who is white, says.

“So that’s why it’s very important for media companies to have people of colour and women and Indigenous people in their management structures, and we just don’t see that. We don’t see that with a lot of media companies.”

Both Moreau and Jolly were cautious around the idea of blanket decisions to not send BIPOC journalists to rural, white towns. For one, it opens the employer up to a discrimination complaint under the Human Rights Act, Moreau explains.

But they agree that sending them alone is not a good idea, and that a “balance” needs to be struck between the need to diversify white newsrooms and the need to keep journalists safe.

“How do you balance that? I wouldn’t want to put someone in harm’s way,” says Moreau. “But I also think communities that are mostly white need to hear from folks that aren’t white.”

Moreau says while some progress has been made in terms of internal policies against worker-to-worker discrimination, newsrooms still “don’t have policies in place and don’t know how to handle a member of the public harassing” their journalists.

Jolly pointed to the CAJ’s newsrooms survey, adding that “it’s going to require candid and messy and uncomfortable conversations, but ultimately it’s about helping journalists tell the stories that need to be told.”

Learning experience

Though Hemens continues to write as a freelancer in Kelowna, he admits the experience has affected him deeply and made him question if the profession and all that it has invited is “worth it,” leaving him “disheartened.”

But ever the optimist, he has taken it all as a “learning experience” worth sharing to help others avoid the same peril.

“It showed me that, you know, people can be very cruel… (and that) higher-ups don’t really have a full grasp on what it means to be a BIPOC journalist in small towns,” he says.

“I want to let people know this is what really happened. People need to know to prevent this from happening again, because I’m sure it’s bound to… So, hopefully people can learn from something that happened.”

EDITOR’S NOTE

This story is about the challenges faced by a BIPOC journalist working in a small town who was subjected to vitriolic comments by anti-vaccine proponents, with some relating to race.

The issue of systemic racism is of great importance and must be told. New Canadian Media and Black Press Media are in no disagreement on this fact and wholeheartedly support reporting by and about racialized persons and their experiences.

These experiences have often been missing, diminished, or dismissed in Canadian news media. As underscored in the story, that is why reflecting these experiences and viewpoints is crucial to providing Canadians with quality, accountable journalism.

That said, this story did not include important information and context to provide readers with a complete picture of the situation reported. NCM now understands that the employers declined to be interviewed because of employer/employee confidentiality.

However, in such cases, it is incumbent upon journalists to find corroborating evidence to support information and allegations that may be injurious to those named in a story. Such evidence and steps were not presented to readers at the time this story was published. NCM has therefore made slight revisions to the original version and offers the following acknowledgements to correct the editorial record.

Specifically, New Canadian Media acknowledges:

- The reporter was not “sent” to Creston but was offered the job after applying for the position. Denying BIPOC journalists from achieving positions in small, rural communities would be racial discrimination.

- Black Press Media has stated its employees are provided training in the company’s Violence and Harassment in the Workplace personal safety policies.

- Black Press Media has stated it provided HR support as soon as concerns were reported to senior management, and the transfer request was expedited as quickly as possible.

- The original story speculated about the motivation of Black Press Media management but did not provide supporting evidence.

- The reference to Black Press Media’s management structure in the original story was untrue, and the company states that in fact there are numerous BIPOC and female managers within Black Press, throughout all departments.

Without the above context, the story did a disservice not only to the reputation of the employer but also failed to show to readers the depth of the issue at hand. This additional information was not available at the time of publication, but NCM recognizes that we have a journalistic responsibility to ensure the ongoing accuracy of all published content and update information as soon as we identify errors and/or receive new information.

Neither NCM nor Black Press cast doubt or aspersion on the journalist’s personal experiences and feelings. He has an important story to tell about being a racialized reporter working in a small community, and the challenges that represents.

Fernando Arce is a Toronto-based independent journalist originally from Ecuador. He is a co-founder and editor of The Grind, a free local news and arts print publication, as well as an NCM-CAJ member and mentor. He writes in English and Spanish, and has reported from various locations across Canada, Ecuador and Venezuela. While his work in journalism is dedicated to democratizing information and making it accessible across the board, he spends most of his free time hiking with his three huskies: Aquiles, Picasso and Iris. He has a BA in Political Science from York University and an MA in Journalism from Western University.

Very poor, bigoted, divisive and potentially libelous article.

Seriously. I used to come to this site for some interesting stuff that wasn’t covered elsewhere. But if it’s also going in the direction of the woke hysteria perpetuated by over educated brats I’m out.