The world is still catching up to Inuit activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier.

A year before being appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2006, she presented a landmark legal petition to the Inter-American Council on Human Rights, linking the disastrous impact of climate change to human rights in the Arctic and urging the United States to set emissions limits and work with Inuit communities.

“Today, it’s mainstream language – everybody talks about [climate change] as a human-rights issue,” said Watt-Cloutier in 2010, when she was a teaching scholar at Bowdoin College’s Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center. “I think we’ve been successful in changing the discourse on this issue to making that connection.”

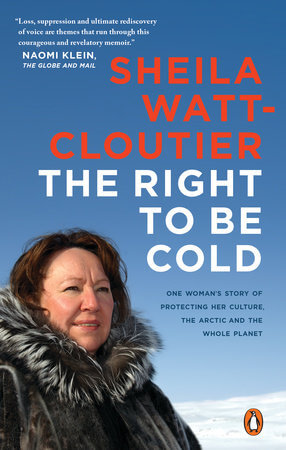

Her book The Right to Be Cold: One Woman’s Story of Protecting Her Culture, the Arctic, and the Whole Planet was released last March. Later in the year, a UN Report on the same subject was presented at the Paris Climate Summit, stating that climate change and human rights are intricately linked and that recognizing this connection will help protect the fundamental rights of communities and people across the planet.

The book was a finalist for the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing in 2015 and British Columbia’s National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction in 2016.

Her story evolved with the discovery of her own strength and power through disappointments and losses.

Uprooted

Watt-Cloutier’s story begins in the hunting and fishing village of Kuujjuaq, a coastal Inuit community in Northern Quebec’s Nunavik region.

“During the short summer months, cloudberries, blueberries, arctic cranberries and black crowberries grow among the green leaves and tundra . . . In the winter, the landscape is transformed into a brilliant vista of ice and snow that stretches under the vast expanse of the blue Arctic sky.”

At the age of 10, Watt-Cloutier was sent south to be “educated.” She struggled with being away from her mother, grandmother, and the land that nurtured her, but later admitted that the experience of separation helped shape her role as an activist in defending and promoting the “northern” way of life.

Watt-Cloutier’s personal story and her message of our interconnectedness are powerful not because she went through a single life-changing event. Her story evolved with the discovery of her own strength and power through disappointments and losses.

Like many young people, she had high hopes for herself. She dreamt of being a doctor and worked hard to meet that goal, yet it remained elusive.

When the eco-system in the Arctic erodes and gradually melts away, so too goes the Inuit people’s cultural identity.

Watching home disappear

Watching home disappear

After returning home from Churchill, Manitoba, Watt-Cloutier worked as an interpreter, educator, and eventually a community advocate. Within her own generation, not only did she witness how environmental degradation and global warming took away her people’s identity as hunters and trekkers, but also how it stripped them of their dignity and physical health.

As an immigrant from a former British colony, I do not need my environmental hat to understand the frustration and helplessness Watt-Cloutier felt as a young girl, witnessing the rapid disappearance of her traditional way of life in Canada’s North.

For the Inuit people, everyday life is tightly knit with their natural environment – hunting, fishing, travelling by dogsled. When the eco-system in the Arctic erodes and gradually melts away, so too goes the Inuit people’s cultural identity.

With colonization, climate change, and toxic pollution, the cold and pristine northern country Watt-Cloutier knew so well was quickly disappearing along with the melting ice and snow.

“What’s happening today in the Arctic is the future of the rest of the world.”

Linking global communities

Watt-Cloutier’s big break as a national and international advocate for the Northern indigenous people came when she was elected to lead the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), representing Inuit people from Canada, Russia, Greenland and Alaska. Working closely with allies and NGOs, the ICC focused on negotiating a global treaty that would ban toxins known as POPs – persistent organic pollutants that travelled airborne from factory smokestacks in the south to the north.

Toxins leaving factories travelled fast in hot air. When they reached the cold North, they would freeze and stay there.

Northern wildlife tends to store more fat, and as it turns out, these toxic particles did well in fatty cells. They survived in the seals and whales that were eventually hunted and consumed by Northern indigenous people.

When an Inuit mother breastfed her babies, the toxins were passed on to her children, ultimately harming the health of the entire Northern population. Watt-Cloutier’s campaign ended with the signing of the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants to eliminate or restrict the production and use of POPs.

Today, Watt-Cloutier continues to do what she does best – fighting for the rights of her people to live in a healthy environment. And she will fight the way she knows best – with strong words, clear ideas and succinct translation.

“What’s happening today in the Arctic is the future of the rest of the world. In one lifetime, we Inuit have seen our physical world transform, the very ground beneath our feet shifted dramatically . . . As we head into stormier seas, we must ask ourselves, ‘If we cannot save our frozen Arctic, how can we hope to save the rest of the world?’”

Winnie Hwo joined David Suzuki Foundation’s Climate Change Team in 2010 after a long and stellar career in journalism. She is passionate about Canada’s multicultural policy and healthy environment.