After more than three years of a pandemic and dealing with a litany of lingering effects, Canadians are understandably concerned about their health and the state of our healthcare system.

According to an Ipsos poll, 35 per cent of respondents indicated that significant investments in healthcare was one of their top priorities for the federal budget ahead of its release last month. The Liberal’s 2023 federal budget contained just that.

Nearly 70 per cent of the $43 billion in net new spending announced in the budget is allocated for health and dental care over the next six years. Earlier this year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also cut landmark deals with all the premiers to substantially increase the amount of money their governments will receive via the Canada Health Transfer in coming years.

While the investments are widely seen as a positive step, some experts and health care workers worry that the spending outlined in the budget won’t go far enough to address inequities in these settings.

In a statement released by the Canadian Medical Association, president Dr. Alika Lafontaine said investments that address worsening patient access to health services “have never been more needed.”

Dr. Semir Bulle, a psychiatry resident at the University of Toronto and co-founder of Doctors for Justice in Long-Term Care, said patients’ ability to access health services and navigate the healthcare system should be a priority. He believes Canada’s health care system is “very paternalistic.”

In an interview with New Canadian Media, Dr. Bulle underlined how important it is for patients to have confidence in the health care system in order to have better outcomes — We know preventative healthcare is the best,” he said — but this confidence is missing in many cases due to ongoing discrimination in health settings.

Bulle, who is Black and Canadian-Ethiopian, remembers a saying he heard growing up: “Go to the hospital, end up dead.”

He explained the prevalence of stories about neighbours going to the hospital and dying or deteriorating within weeks or months but their loved ones not being told why. It’s hard to prove the validity of anecdotes like these, he said, but stories about negative patient outcomes permeate and foster distrust.

Distrust can lead to worse health outcomes as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 misinformation led to at least 2,800 deaths and 198,000 additional infections between March-November 2021, according to a recent report from the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). The report, published in January, found that around 2.3 million Canadians were influenced by misinformation, fuelling their vaccine hesitancy.

Inequity in healthcare

Discrimination is also a factor in negative health outcomes that contributes to distrust.

Dr. Avnish Mehta is a family physician at the Scarborough Centre for Healthy Communities and chief of family medicine at Scarborough Health Network (SHN). According to him, physicians hearing from patients who felt like they’ve been discriminated against in the past by the health care system is not uncommon.

“They’ve had experiences where they felt because of their ethnicity, their race, or even their socioeconomic status, that they weren’t treated the way others were,” Mehta explained. “When people experience discrimination in the health care system, they’re less likely to want to engage in the health care system in other places.”

Both Mehta and Bulle worry that avoiding the healthcare system due to discrimination could also lead to negative health outcomes through things like delayed cancer screenings or treatments.

In October, a study from the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto found that regularly experiencing discrimination is associated with being nearly twice as likely to have a chronic medical condition. Researchers noted that Black and Indigenous Canadians are “far more exposed to experiences of discrimination” than other groups.

Re-establishing community trust in healthcare

Raised in Rexdale, a heavily-racialized, immigrant-dense Toronto suburb, Bulle says most people didn’t have a family doctor or know how to navigate the healthcare system. One of the recommendations from the CCA’s report is greater emphasis on effective communication of health information and reaching diverse audiences.

Mehta mentioned a program called Vax Facts where community members book an appointment with a physician to discuss their COVID-19 vaccine concerns. SHN also enlisted the help of the Black Physician Association of Ontario in their vaccine rollout. Mehta said these initiatives were “integral” to SHN’s vaccination campaign and “well-received” by the community.

These programs were crucial for reaching racialized communities hit hard by the virus. Data from the first few months of the pandemic showed BIPOC accounted for 83 per cent of COVID-19 cases in Toronto, despite making up roughly half the population. In Scarborough, visible minorities make up 74 per cent of the population and 59 per cent of residents are new Canadians, according to SHN Foundation data.

“We strive for a healthcare system where everyone is treated equally but increasingly, we’re seeing data which doesn’t support this,” Mehta said.

Scarborough could have a program specifically designed to break this cycle of distrust, discrimination and poor health outcomes for marginalized communities by 2026. The Scarborough Academy of Medicine and Integrated Health is expected to be a community-centric expansion of the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) medical and healthcare education programs.

One of the program’s objectives is to increase the number of healthcare professionals trained and eventually working in eastern Toronto.

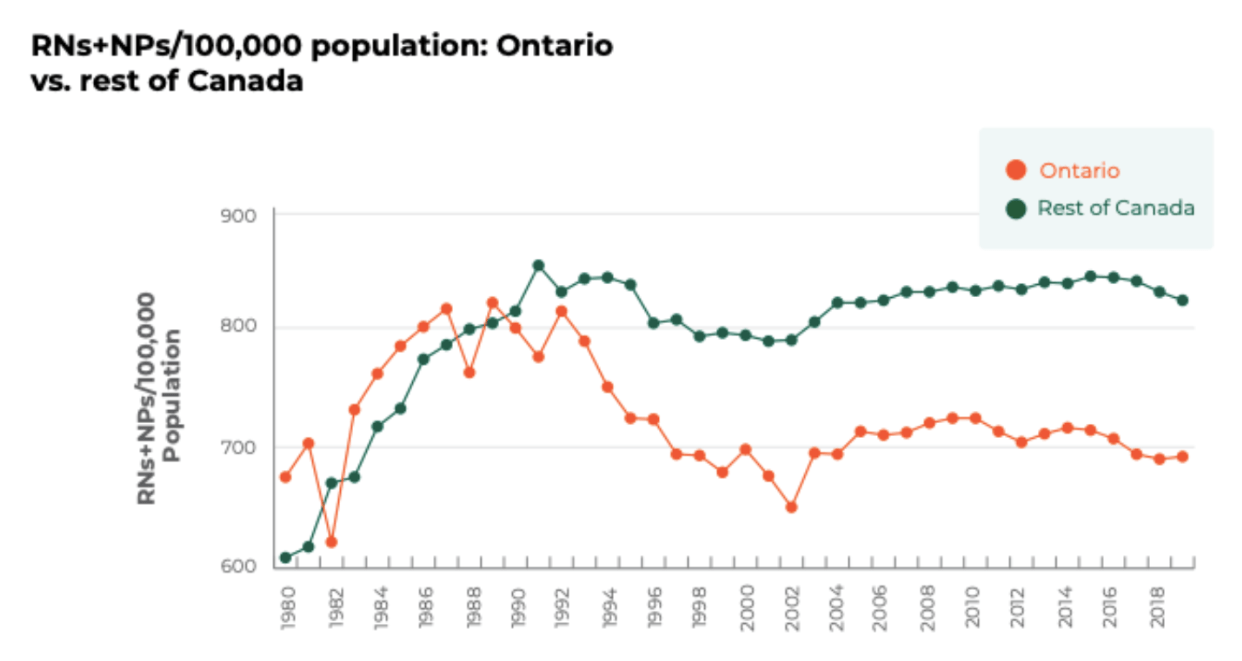

According to the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, the number of nurses per 100,000 residents in Ontario has been below the national average for decades.

The program is also emphasizing how social determinants of health like poverty and systemic racism impact people’s health. It is expected to usher in “a new way of educating health-care professionals,” that views health as more than just a biomedical issue.

Moving forward with equitable healthcare

Mehta is excited about the Scarborough Academy of Medicine and Integrated Health because it’ll offer healthcare providers an opportunity to “expand our knowledge of health equity, enhance our ability to reduce disparities and promote health in our community.”

“Identifying gaps is step one,” Mehta said. “Step two is identifying the reasons—that’s going to involve more quantitative and qualitative research. Step three is taking that information and moving forward.”

Bethlehem Teshome, a first-year student in the Psychological and Health Science Program at UTSC, shares Mehta’s enthusiasm about the academy. She has wanted to be a doctor since she was eight-years-old and now plans to major in population health with a double minor in biomedical ethics and health humanities.

Teshome believes learning about the discrimination patients face is important for health care workers and hopes they understand “what can [they] do to make sure that when [patients] come to us that they feel heard and acknowledged for who they are.”

Teshome knows the academy is not a silver bullet solution to ending discrimination in healthcare but believes a better system is achievable.

“There are a lot of gaps and more gaps will keep coming until we address those gaps in the first place.”

Marcus is a poet, editor and freelance journalist based in Toronto. He currently works with New Canadian Media as an Editor and as a Freelance Writer for ByBlacks.com, The Edge: A Leader's Magazine and The Soapbox Press.