Making distant readers empathize with historical events they have not experienced is a challenging feat.

Making distant readers empathize with historical events they have not experienced is a challenging feat.

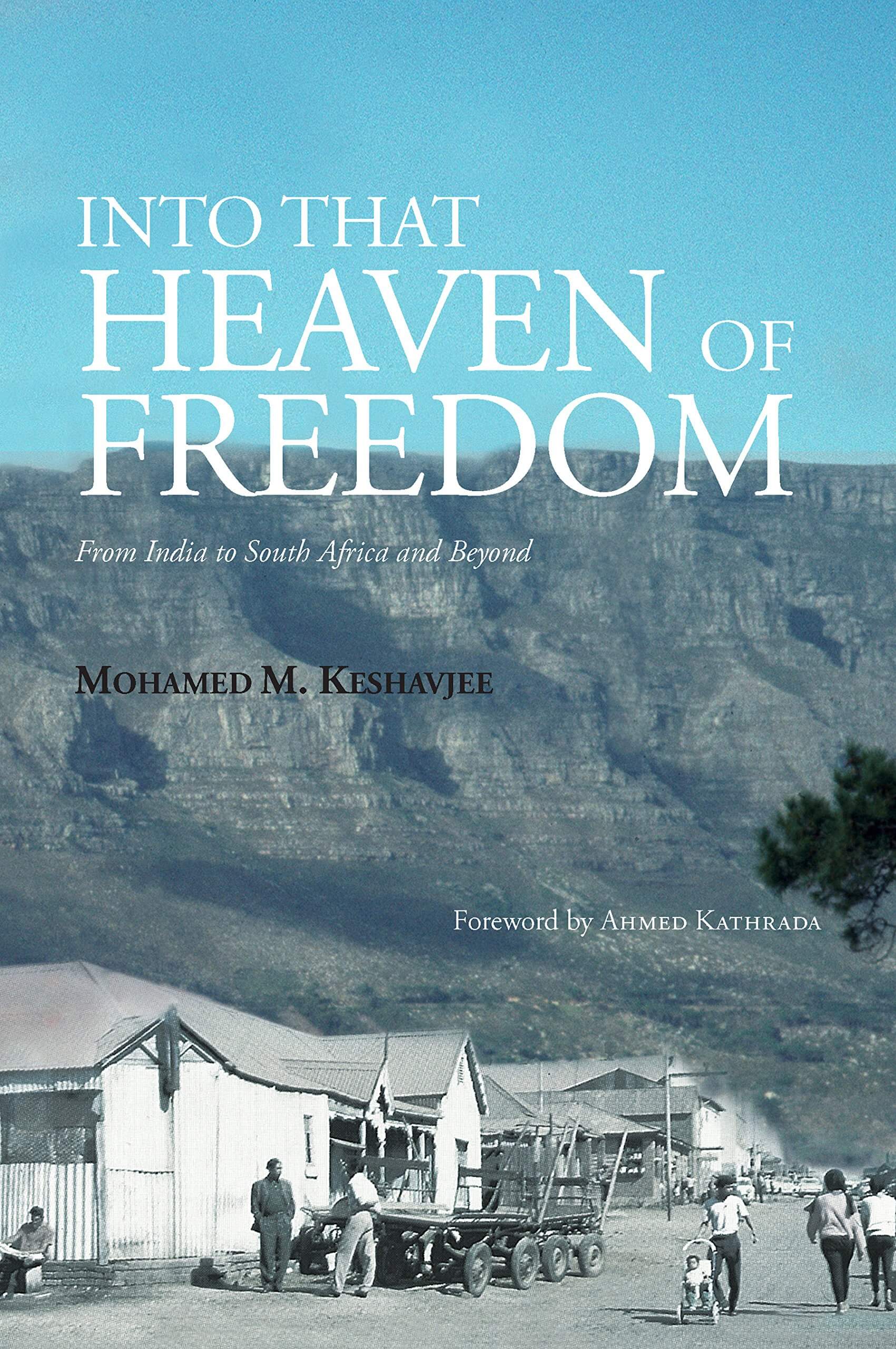

Mohamed M. Keshavjee grapples with getting individuals to feel the pain of the global collective and experience events that they have not been touched by in his latest book Into That Heaven of Freedom: The Impact of Apartheid on an Indian Family’s Diasporic History.

Keshavjee, a second-generation South African of Indian origin, not only takes readers through his own family history, but also through the history of Indians living in Africa over the course of a hundred years.

The title comes from Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore’s poem “Where the Mind is Free:”

“Into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.”

The poem is part of Tagore’s Nobel prize-winning poetry collection, Gitanjali. The book also has a forward written by Ahmed Kathrada, who spent 26 years in prison with Nelson Mandela and is the longest serving human rights prisoner alive today.

Path to self-discovery

We are merely there for the ride as Keshavjee takes his own journey through history.

Keshavjee describes the political struggle against apartheid, beginning with his roots – his family’s establishment in 1894 in Marabastad, a settlement in Pretoria, South Africa. He then describes Mahatma Gandhi’s fight against racism during the beginning of apartheid. Keshavjee’s family continues its journey to Kenya and eventually relocates in Canada.

While Keshavjee writes with authority and knowledge, lurking behind every page is also the realization that he is discovering his own role in this narrative and not merely uncovering the role of his family in history. It is as much self-realization as it is storytelling. We are merely there for the ride as Keshavjee takes his own journey through history.

While Keshavjee writes with authority and knowledge, lurking behind every page is also the realization that he is discovering his own role in this narrative and not merely uncovering the role of his family in history. It is as much self-realization as it is storytelling. We are merely there for the ride as Keshavjee takes his own journey through history.

At the onset of the book, Keshavjee states: “If I have started a conversation amongst my readers about their own antecedents and their personal recollections, I shall be happy.”

However, as I continued reading his memoir, I began to suspect that the most important conversation Keshavjee would have as a result of this storytelling is with himself, about who he really is as he grapples with finding out who he was not in the country of his birth, and who he was in the country of his ancestors.

It is by watching his journey that a reader can hope to embark on the same one through their family’s history.

Recording history

Where readers might get lost is in the minute details – names of brothers, cousins’ shops, and small communities, each explained in heavy detail throughout, which sometimes feels as if one is reading a classroom history book – ironic for Keshavjee who writes that as a child, he looked forward to the time when he would no longer have to attend school.

Each new chapter brings with it new characters who are all part of Keshavjee’s history. While the story could have been told without some of those details, it is again evidence of the author’s desire to record the names, dates and places of those that came before him, struggled before he did, and persevered to allow him to find his own place, too.

“I am grateful that, unlike my ancestors, I have been able to tell my story.”

Childhood impressions

Although the book is very much a journey, it hints at the times in Keshavjee’s life when he did start to locate his place in the world. It’s the 1950s when Keshavjee starts to like school and impresses his teachers with his creativity and talent.

In the childhood stories he writes, “Autobiography of a Penny” and “Autobiography of an Old Shoe,” Keshavjee imagines himself as the coin or shoe and the many places it might have been placed, the people who might have touched it, and the home it ended up in.

These stories, although only mentioned over the course of a few lines in this almost 300-page book, foreshadow this memoir, as Keshavjee once again describes the life he has and underneath the surface, the life he might have had, had he been born in a different country, to a different race, with a different skin colour.

Today, Keshavjee is a graduate of Queen’s University and the School of Oriental and African Studies at London University, among several other academic achievements. He was called to the bar at Osgoode Hall in Toronto and is a member of the Law Society of Upper Canada. He also practised law in the United Kingdom and Kenya, and served in the Secretariat of His Highness the Aga Khan.

His success is apparent as the memoir winds down and Keshavjee seems to find his answers.

“I am no longer a refugee in search of a homeland,” he writes. Perhaps that is not just because he has found a physical home, but a metaphorical one too in this book. As he notes, “I am grateful that, unlike my ancestors, I have been able to tell my story.”

Vicky Tobianah is an experienced writer, editor and content strategist. She has a bachelor of arts, honours from McGill University in political science and English literature. She is passionate about the future of digital media. Find her work at: www.vickytobianah.com