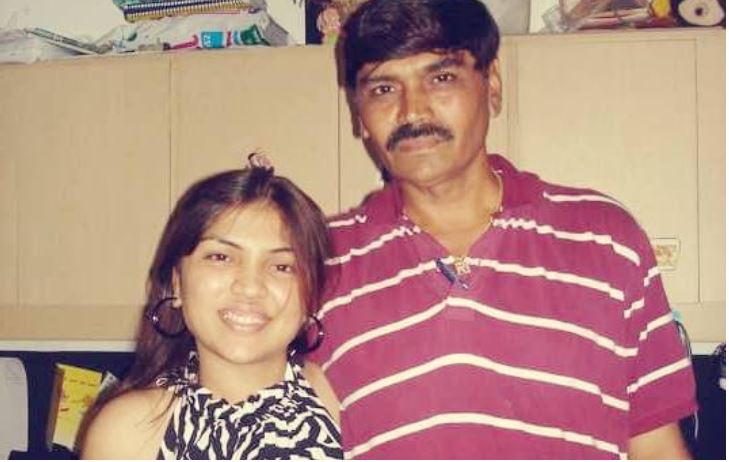

In May, my father, Rajendraprasad Bhatt, passed away in India from a heart attack. Although my father survived cancer, he was fearful of contracting COVID-19. His happiness knew no bounds when he got both of his doses of the COVISHIELD vaccine. At 59, he was determined to survive. Although he didn’t die from the virus, the pandemic robbed me of the chance to say a meaningful goodbye. His death set off a personal struggle to get home to comfort my mother. I couldn’t have fathomed the nightmare journey that would unfold ahead of me.

Before I could grieve his death, I was informed my father’s body would be cremated before my arrival. The pandemic was at its peak in India and by mid-May, COVID-19 was killing more than 4,000 people a day. As of July 17, India’s official numbers show that more than 31 million people have been infected with the virus, while more than 413,000 have died from the virus. But many health officials and experts believe this is an undercount of the pandemic’s toll.

So many people were dying that the crematoriums didn’t have enough space to house the bodies, nor did they have enough supplies of wood and staff to help with funeral pyres. International travel was still banned and I wasn’t sure when I would be able to get a flight out of Toronto. My father’s funeral could not wait for my arrival.

My husband, cousin and I took our COVID-19 tests as fast as we could and booked a circuitous flight home via Abu Dhabi. Our journey to Rajpipla, Gujarat in western India took three days. Those were the longest 72 hours of my life. This was the first time I was seeing an airport during the pandemic. There were few passengers. I stared at every individual and wondered why they were travelling at such a time. Did they lose a loved one just like me?

There are 1.3 billion people who live in India and Rajpipla, the small town where I was born, is surrounded by a dozen hamlets. I knew that given the density of the population it would be difficult to practise social distancing. Because my father didn’t die of COVID-19, people were not as afraid to pay their respects. There was a constant stream of visitors who came to my mother’s home. Some visitors would wear a mask, others did not. My younger sister would try to sanitize each chair they sat on after they left.

As per Hindu rituals, we went to the banks of a nearby river to immerse my father’s ashes in the holy Narmada River. I was startled at the number of visitors we saw there.

“Occupancy at the ghats (the steps leading down to the river) have quadrupled since the pandemic,” said the priest, noticing the anxiety etched across my face. My memory is a blur from that time of grief, but I remember a constant honking of horns as people tried to find a parking space so they could participate in funeral rites. There was a stream of people waiting for the priests to take them out on small boats to the centre of the river. Making matters even more uncomfortable, the heat made it extremely difficult to breathe in the layered masks.

My cousin, Dr. Saurabh Bhatt, works as a pulmonologist (respiratory physician) at a hospital in Bharuch, Gujarat. As a frontline warrior, he has witnessed horrifying stories during this pandemic. As a doctor, he began his day at eight in the morning and worked until midnight.

“On average I alone saw about 300 patients daily when the wave was at its peak. There were times when people would come begging for space in the hospital and I had to blatantly refuse,” Dr. Bhatt said. “We had to shut the doors of our hospitals as we were beyond our capacity.”

Dr. Bhatt says he has been “deeply moved” by how some people went “above and beyond” to get their own critical life-saving equipment like oxygen tanks when the hospital ran out of supplies.

The doctor blames the high death rate on government negligence; social distancing was not enforced and the government did little to combat misinformation about vaccines and COVID that is widely circulated, especially among the poor and uneducated. More than 22 per cent of India’s population is illiterate. Even at our home, the domestic helpers who work for our family refused to get inoculated.

“I have heard you die after your first dose,” said Ambalal, a labourer who is employed at our family farm. No matter what scientific information I give him, he will not change his mind.

After a harrowing spring, Dr. Bhatt says COVID-19 cases are declining in Bharuch and its nearby towns as vaccination rates improve. He hasn’t seen many positive cases in June, and he prays it remains the trend.

My sister was nervous as she had not yet been vaccinated as there was a vaccine shortage in our town. An acquaintance who works at a local health clinic informed us that she could arrange a vaccine for us in an emergency. However, she could not get us an official certificate. Apparently, these were vaccines that were meant only for people from a particular village. But, if by any chance a person refuses to take the vaccine, then they are kept aside and distributed to someone the vaccine administrators select. Because of the vaccine shortage, people were now being told to get their second shot after 84 days instead of 60.

However, from mid-June, cases in my town and nearby cities saw a massive decline. We can partly attribute it to India’s replenished stock of vaccines. The Indian government has ordered 660 million vaccine doses for use in the next five months and says it intends to vaccinate all 944 million eligible adults by December 31.

Slowly the provincial government of Gujarat announced some loosening of restrictions. People are now allowed to eat at restaurants and weddings or functions of 100 people are now permitted in Gujarat. Similar liberties have now been announced in other provinces as well where cases have gone down.

Life appears to be returning to normal, but I worry about my mother. She has worked all her life as a school teacher and has recently retired. Now with my father’s death, she is suddenly alone without a clear path forward. Her retirement plans did not include becoming a widow. I remain at my mother’s side for now. I’m waiting for the Canadian government to open up its borders. I hope to return home with my mother to a post-pandemic Canada where she can begin a new life, far from the tragedy she’s seen in India.

This story has been produced under NCM’s mentoring program. Mentor: Judy Trinh.

Media Professional with over 5 years of versatile experience in corporate communications, content creation, community engagement, report writing, story promotion and effective editing skills. Presenter and writer with a reputation for offering prompt creative initiatives, drafting detailed reports with over 300+ published bylines in national publications. Adept at researching online/offline prospects to actively garner audience’s attention on brand, both offline and online.

So sorry to hear about your loss. Stay safe.