“We’re not going to end racism tomorrow, but we’re sure as hell going to try.”

Winnipeg’s Mayor Brian Bowman spoke those words in an unprecedented and emotional press conference outside his office in January. Bowman was prompted by a Maclean’s magazine cover story that released online the day before, deeming Winnipeg to be “Canada’s most racist city.” More than 30 prominent Winnipeggers – academics, advocates, chief of police, indigenous leaders and city councilors – flanked the mayor as he pledged to change that negative perception.

“I want every young person in our community, regardless of where you come from, to be proud of Winnipeg.” – Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman

“My wife is Ukrainian heritage,” he said, choking back tears. “My family is Metis. I want my boys to be as proud of both those family lines and I want every young person in our community, regardless of where you come from, to be proud of Winnipeg. Be proud of who you are.”

The Maclean’s article, describes Winnipeg as having a, “festering race problem,” particularly against indigenous groups, “who suffer daily indignities and appalling violence.” Instead of defending the scathing critique on the city, Bowman openly admitted there was truth in it — and that he wouldn’t let it persist. In that moment, Bowman’s decision to confront the racial divide head-on was heralded by some as a watershed moment.

Cultural Context

Crack open any Canadian history text and it becomes clear that the underlying racism pervading Winnipeg is largely due to the lasting imprint of its colonial roots.

For example, from the late-1800s to the mid-1990s, thousands of Aboriginal children passed through the residential school system. They were torn away from their families and deprived of their cultures and languages. These were just one of the deliberate attempts made to quash Aboriginal heritage and to enforce the racist belief that indigenous groups were inferior to European groups. Many Aboriginal children died of disease, were physically or sexually abused, and were made to renounce their heritage. It caused the intentional breakdown of families, and subsequently prevented the Aboriginal traditions from being passed down from one generation to the next. And while the trauma endured by those families lingers today in the form of deep-rooted structural racism, today’s cultural make-up of Winnipeg is starkly different from what it was mere decades ago.

According to Statistics Canada’s National Household Survey (NHS), 714,640 people lived in Winnipeg in 2011. Of that total population, approximately 12 per cent (82,700) were of North American Aboriginal descent – the highest percentage of Aboriginal people in any major Canadian city – including members of the Métis, First Nations and Inuit communities. Another 21 per cent (147,295) comprised of immigrants. The Filipino community in Winnipeg is the largest immigrant group. By 2011, 43,390 immigrants born in the Philippines had settled in Manitoba’s capital, making it the Canadian city with the greatest percentage of Filipino migrants (8.7 per cent). A vast majority of immigrants settling in Winnipeg subsequently hailed from India (11,310), the United Kingdom (9,170), China (6,015), and Germany (5,110). Between 2006 and 2011, 45,270 immigrants settled in Winnipeg.

According to Statistics Canada’s National Household Survey (NHS), 714,640 people lived in Winnipeg in 2011. Of that total population, approximately 12 per cent (82,700) were of North American Aboriginal descent – the highest percentage of Aboriginal people in any major Canadian city – including members of the Métis, First Nations and Inuit communities. Another 21 per cent (147,295) comprised of immigrants. The Filipino community in Winnipeg is the largest immigrant group. By 2011, 43,390 immigrants born in the Philippines had settled in Manitoba’s capital, making it the Canadian city with the greatest percentage of Filipino migrants (8.7 per cent). A vast majority of immigrants settling in Winnipeg subsequently hailed from India (11,310), the United Kingdom (9,170), China (6,015), and Germany (5,110). Between 2006 and 2011, 45,270 immigrants settled in Winnipeg.

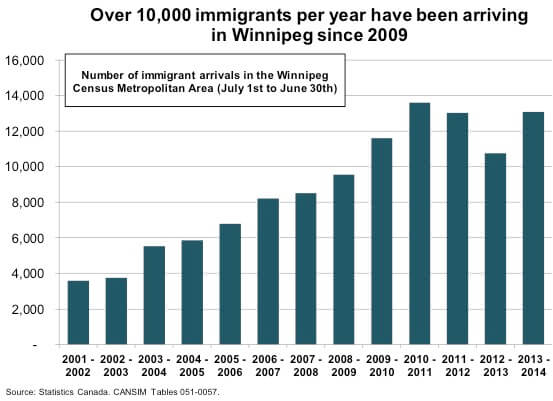

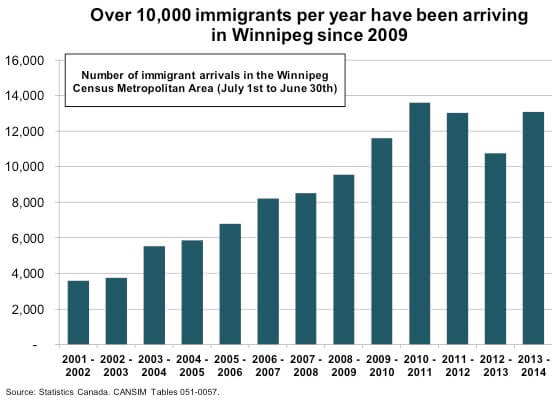

Winnipeg’s police chief Devon Clunis says the city has seen a “massive shift” in its demography since he joined the force 28 years ago, as seen in the Statistics Canada chart to the left.

“When I applied to the police service, I think I might have been the third black police officer hired in our city in 1987,” says Clunis, who immigrated from Jamaica. “We’re not talking about ancient history. Now when you look at the face of the police service, it incredibly reflects the diversity of our city. I’m the chief of police so I’ve seen incredible change in our city in those years.”

The diversity is reflected in the numbers. Between 2001 and 2011, the immigrant contingent in Winnipeg also grew from 16.8 per cent to 17.7 per cent. During that span of time, the percent of visible minorities, or people other than Aboriginal people who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour, jumped from 11 to 15 per cent.

“This generation has the responsibility to help rectify some of those ills of the past and move forward.” – Winnipeg police chief Devon Clunis

Clunis refutes the idea that Winnipeg is Canada’s most racist city, because he says it’s not something that can be quantified, but adds, that doesn’t mean there isn’t much work to do.

“This generation has the responsibility to help rectify some of those ills of the past and move forward,” says Clunis. “That’s what causes the disparity, but to use the term we’re the most racist city — I don’t really buy that.”

One Winnipeg

In the days following Bowman’s January announcement, the mayor launched 1winnipeg.ca — a website designed to solicit ideas from virtually anyone on how to curb racism in Winnipeg. Nearly a month later and there are approximately 160 comments on the page, ranging from backlash over the statement that Winnipeg is riddled with prejudice to ideas as to how to curb the perceived levels of ignorance.

One commenter insists, “Blaming bad Aboriginal outcomes on ‘racism’ is a lie and a cop-out.” Another brings reverse-racism into the fold adding, “I am so sick of hearing Aboriginals crying for more handouts. There are more incentives for Aboriginal people than any other group of people, and that in itself is racism.”

“Eradicating racism is an unrealistic goal I think, unfortunately… The goal is to bring communities together so that the racists amongst us will be clearly labeled as such and excluded from the conversation.” – Anita Bromberg, Canadian Race Relations Foundation

But some ask if there’s any merit to the new site — or if it’s simply a glorified suggestion box.

“If all they’re going to do is put up the website and pat themselves on the back, we’ve seen other websites that have tried to deal with racism,” says Anita Bromberg, executive director of the Toronto-based Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

“That’s not enough. I have every hope [the] mayor has got the will and the determination that [this] should only be one small step in looking forward,” she adds, insisting the website should only be one measure.

“I think the conversation is the most important way to deal with racism. You take it from under the rug and you shake out the rug and you start a conversation,” says Bromberg.

“Eradicating racism is an unrealistic goal I think, unfortunately. But history has proven it may not be the goal,” adds Bromberg, who adds she grew up in Winnipeg and says she was the victim of racial attacks in the past. “The goal is to bring communities together so that the racists amongst us will be clearly labeled as such and excluded from the conversation.”

“I would hope the city, or the province, or the community in general, makes a concerted effort to put some of those ideas [into action], take them from the imagination and bring them forward to a reality.” – Matthew Bzura, 1Winnipeg.ca user

While some native Winnipeggers aren’t convinced this alone will bring about change, others are confident Mayor Bowman’s new website is a smart approach.

“He’s running on a platform of openness and transparency and he’s a very active social media user,” says 23-year-old business student Matthew Bzura, who volunteered on Bowman’s mayoral campaign.

“Whether it’s good or bad, he likes to hear everyone’s opinion, on matters such as these,” says Bzura. “It’s a very strategic move.”

Bzura was born in Winnipeg to a Polish immigrant family. He says the website is a way for people to air out their thoughts and, “see what Winnipeg stands for.”

“I would hope the city, or the province, or the community in general, makes a concerted effort to put some of those ideas [into action], take them from the imagination and bring them forward to a reality,” he says.

Facing Racism Head-On

Bzura pitched one such idea that made it to the website (as seen in slideshow below). He suggests the city host a comedy show starring some of the biggest comedians in the industry, such as “the Aboriginal King of Comedy” Howie Miller and the hugely popular Russell Peters, with a pre-amble or post-show chat about the issue of racism as it pertains to Winnipeg. He even has a working title for it: Confronting Racism with a Smile.

“Whether it was a bully, whether it was a tragic event like a death, comedy was always a good remedy for my spirit,” says Bzura. “It was a good way to deal with a very confrontational idea or situation and take the awkwardness out of it… and God forbid, put a little bit of humour into it.”

Fostering that conversation is something the Canadian Museum for Human Rights has also encouraged on 1winnipeg.ca. The new museum, which opened last September, but is just four weeks into educational programming, expects to welcome over 21,000 students between now and June.

“Attitudes and behaviours begin so young and if you can just open somebody’s eyes at a young age, they’ll remember it,” says the museum’s learning and programming director, June Creelman, who explains in one activity students learn about various human rights defenders, which prompts them to reflect back on their own lives.

“Sometimes the kids are wiser than we are,” she says with a chuckle, sharing an incident with a five-year-old and an adult, in which the adult exclaimed how they hated something — to which the child responded, “hate is a very strong word.”

Moments like these happen all too frequently at the museum, says Creelman, but a particularly poignant one happened during a conversation a 10-year-old girl had with her mother, after taking part in a program about the First Nations.

“The young girl was talking about how she felt bad about racism and this [Maclean’s] article,” says Creelman.

“But she went on to say that one day, she hoped that racism would be like the dinosaurs. They’d be only bones,” she adds. “They wouldn’t deny that it [happened], but it would be a distant memory. Somehow that really got to me as such a good wish for the future.”

Chief Clunis says the Maclean’s article may have been out of line with calling Winnipeg as most racist, but it has sparked a sensitive conversation that’s been tiptoed around for some time. The tweet showcased to the right is just one example of why ethnicity, race and culture remain pressing matters for discussion amongst Winnipeg residents.

“If it does raise the conversation in our city and we start looking at each other in maybe a more compassionate way, that’s a good thing,” he says.

Clunis reflects on his own experiences, adding, “Everyone has to have the same opportunity that this little boy from Jamaica had to achieve, and right now, we don’t have that for everyone in our city. So I’m saying, we collectively need to work towards that.”

He insists things will change, because they have to.

“I believe our city of Winnipeg will transform in terms of the equity of opportunities and relationships that you will see in the city,” says Clunis. “Because that’s the future. If we don’t do that for our city, we won’t become all that we can be.”

Stay tuned for the rest of this three-part series. Next, we will examine Winnipeg’s immigrant and visible minority communities to explore where they think Winnipeg sits on the racism barometer.