Canada’s most seasoned academic on immigration, Prof. Jeffrey Reitz, suggests that the decision of the government to postpone and reduce reliance on employer participation in the Express Entry system that takes effect Jan. 1 is simply a recognition of reality. Maintaining a leading role for government selection is the only way to ensure that Canada continues to receive an average of 250,000 new immigrants every year, he said in comments over the weekend.

Canada’s most seasoned academic on immigration, Prof. Jeffrey Reitz, suggests that the decision of the government to postpone and reduce reliance on employer participation in the Express Entry system that takes effect Jan. 1 is simply a recognition of reality. Maintaining a leading role for government selection is the only way to ensure that Canada continues to receive an average of 250,000 new immigrants every year, he said in comments over the weekend.

In his view, short-term employer needs are not a good enough or efficient substitute for a system that has so far largely relied on the general employability of newcomers – also called the “human capital” model. Faced with mounting evidence that successive waves of immigrants are faring badly, the Conservative government has put in place a series of moves designed to increase employer participation to determine who gets in.

The eventual goal of this approach is to grant permanent residence under the “economic class” only to those who have a pre-arranged job offer in Canada. Reitz, affiliated to the University of Toronto’s prestigious Munk School of Global Affairs, though, has his doubts about relying on employers as a proxy for government or a neutral points system to fulfill the bulk (60 per cent) of Canada’s immigration needs.

[Broadly speaking, Canada’s quarter-million newcomers fall into one of three classes – economic, family unification and refugees, split traditionally at 60:30:10 per cent, respectively.]The U.S, he said, attracts from 150,000 to 175,000 a year under a ‘pre-arranged job’ category, while Canada can expect 15,000 to 17,000 annually – almost certainly causing a huge gap in Canada’s annual target of attracting 250,000 new immigrants every year. Of the 250,000 new arrivals, 60 per cent fall under the economic class (including immediate family members), with roughly 65,000 being “principal applicants” who qualify based on their work experience, language skills and general employability criteria.

Interestingly, Reitz points out, a number of changes introduced in recent years have been modelled on Australian reforms introduced by the then John Howard government a decade ago, in the hope that more new immigrants will be employed from the day they land in Canada. “[T]he evidence for the success of the Australian initiatives was based primarily on short-term outcomes, and analysis of the overall performance of immigrants in Australia does not suggest that the new policies produced any overall improvement.”

Global experience

New Canadian Media interviewed Reitz in the context of the 2014 edition of Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective (Stanford University Press), an academic publication that is now in its third edition and includes policy reviews on every major immigrant-receiving nation.

“Nobody has had success” with this sort of employer-driven immigration system to produce large-scale immigration, the academic who has been tracking immigration trends in Canada and globally for four decades, said. The book has a chapter devoted to Canada, and in this Reitz writes: “Indeed, the Australian government has greatly reduced visa opportunities for international students and is reviewing its selection policy more generally.”

Overall, he writes in the book, “… it is far from clear that the new policy directions [in Canada] will actually improve the prospects for and impact of immigration.”

The UofT professor points out that while the jury is still out on the key question of net economic gain, Canadian newcomers can be expected to reduce income inequality mainly because they tend to be employed in high-skills jobs rather than at the lower end. “Immigrants compete for more highly skilled work in Canada, so the labour market impact is at levels of employment higher than the impact of relatively less-skilled immigrants in the United States.”

Income inequality has been a hot topic of political debate in both the U.S. and Canada in recent months.

Immigrant credentials

Reitz also attempts to mathematically calculate the extent to which immigrant credentials are discounted in Canada: “[I]mmigrant skills in terms of both education and work experience have only about two-thirds of the value of corresponding skills held by native-born Canadians, and occupational under-employment is a significant reason for this imbalance.” This is based on a statistical calculation made by labour market analysts on the return on investment (ROI) that Canadians gain from every additional year of education.

Studies have shown that while mainstream Canadians gain five per cent in added earnings for every year of education, newcomers boost their average pay by just 3.5 per cent. “Some analysts have noted a decline in return for foreign experience as well, although no explanation for this trend has been found.”

The book chapter on Canada notes that the issue of immigrant credentials is today no closer to resolution: “There is as yet no overall plan to address the problem, which is certain to remain significant for many years.” Acknowledging that the availability of credential assessment services and bridging programs may be making a difference, Reitz, however, points that there has been “no effort to evaluate the overall impact of all these programs in relation to the problem of immigrant skill under-utilization.”

Further, Canada’s been receiving even more qualified immigrants in recent years. “If anything, the problem of immigrant employment in Canada has become more difficult over time, and it is more serious today than it was when it was first identified in the 1990s.”

Support for immigration

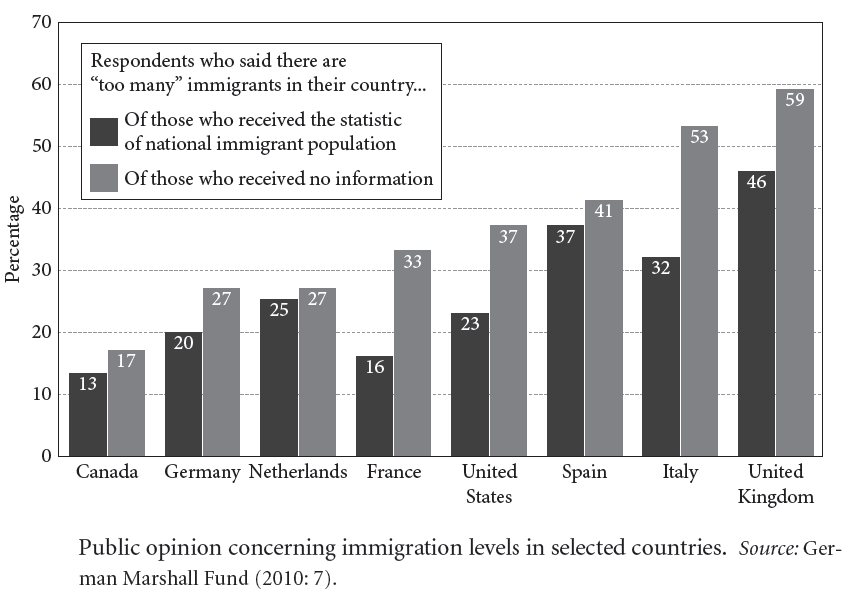

The 10-year retrospective in the book also has a section devoted to public opinion on immigration and politics. It points to the creation of the Centre for Immigration Policy Reform and the presence in Canada of a “distinct minority” that opposes the current level of immigration. Reitz takes issue with those who claim that majority support for immigration levels is a “myth”. Further, he adds, “Those who want to reduce immigration levels in Canada are very clearly the minority and have been for some time.”

In separate comments, the academic believes Canada has built up a “resilient base of support” for immigration and he does not foresee a shift in attitudes happening any time soon.

Here are some more nuggets from the book chapter entitled “Canada: New Initiatives and Approaches to Immigration and Nation Building”:

- On immigrant settlement: Government statistics indicate that each immigrant receives about $3,000 worth of settlement services

- On the politics of immigration: The Focus Canada survey showed that Conservative party supporters are significantly less likely to support immigration, based on their socially conservative values.

- Ethnic vote: “The Conservatives have sought support among immigrants based on [socially conservative] values and, despite some success, have experienced difficulty because some of their related policies on multiculturalism and citizenship portray immigrants as a threat to traditional Canadian values.”

- Immigrant integration: most analysts attribute successful integration to the fact that newcomers tend to be highly educated and skilled, and not necessarily to multiculturalism. Conversely, a decline in skill and education levels can be expected to have the opposite effect.