Much ink has been spilt on Canada’s slow-motion efforts to resettle the promised 40,000 Afghans fleeing atrocities under Taliban rule. But hampering the efforts of aid organizations to bring life-saving supplies to 25 million poverty-stricken Afghans is an even a more egregious failure, say officials of Canadian non-governmental organizations or NGOs. Stringent anti-terrorism laws aimed at the Taliban are, in fact, hurting the Afghan people, they insist.

The Taliban is listed a terrorist organization, and under Canada’s anti-terrorism laws any financial transactions that send money into the coffers of such organizations are illegal and those who violate the laws are liable for prosecution.

But the reality is that the Taliban is the de facto government of Afghanistan, and this anomalous situation leaves NGOs—such as One Free World International and World Vision —with nearly insurmountable challenges, because everything from buying gas to renting apartments to paying staff salaries results in money going to the Taliban government.

“Afghans—those left behind after tens of thousands fled the country in a terrified exodus after the fall of Kabul on August 15, 2021—are facing the worst humanitarian crisis of our century,” Majed El Shafie, president of One Free World International, a Toronto-based NGO told New Canadian Media. “These laws are not punishing Taliban militants. They (Taliban leaders) are doing fine. The restrictions are punishing Afghan people.”

El Shafie, who has been to Afghanistan and other global crisis spots several times for humanitarian work, is planning to go back to Afghanistan on another mission in September. He will be accompanied by a member of the European Union parliament who is the advisor to a European Union committee on alleviating the effects of the economic collapse in Afghanistan.

Before the US withdrawal of troops and the fall of Kabul to Taliban militants, 45% of Afghanistan’s GDP came from foreign aid, according to the World Bank. About 75% of public spending was funded by foreign aid grants.

But this assistance has now been withdrawn, since most nations don’t recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

Besides arguing that freezing of assets and international aid —intended to halt the flow of money to the Taliban—is making collateral victims of the Afghan people, El Shafie has dire warnings about hunger in Afghanistan.

“Children are facing death from hunger, and more than half the population relies on humanitarian aid for survival,” he said. “If it continues like this, it will not only affect the people of Afghanistan, but will have serious geopolitical consequences. The governments of Russia, China and other non-democratic countries will fill the vacuum left by democracies like Canada, and will become allies of the Taliban government which cannot meet the basic needs of their people.”

Describing the extreme danger that he and other humanitarian aid workers face, he said that by going to Afghanistan he runs the risk of being killed by the Taliban as an apostate, since he is a convert from Islam.

“When I come back to Canada, I might be arrested for breaking the law and providing food, clothing and medical supplies to Afghan refugee camps on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, which is under Taliban control.”

He has a message for the Canadian government: “Find a way to solve this dilemma, and allow NGOs to operate in Afghanistan with transparency and accountability.”

He added that Canada is notorious for sending millions of dollars in aid to various countries without ensuring accountability, and this has to stop. Between April 2020 and March 2021, Canada sent $153 million in aid to Afghanistan.

“The US and many European countries have solved this issue balancing the need to punish the Taliban and helping the Afghan people, because they have understood the urgency of the situation,” he pointed out.

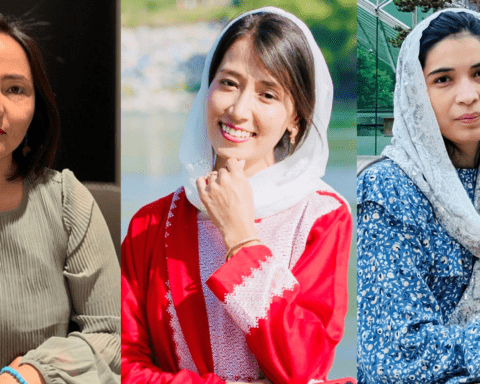

Fatima Quereshi (not her real name since she requested anonymity for fear of retribution) is an Afghan woman who lives in Toronto. A recent arrival, she fled her country shortly after the Taliban takeover. As a woman, a journalist and women’s rights activist, she was lucky to escape death at the hands of the Taliban and find asylum in Canada after singlehandedly negotiating the labyrinthine process of securing a visa through the Canadian embassy in Pakistan. Today, she has a contract position in public relations and is immensely grateful to all the Canadians who welcomed her and helped her begin a new life in Canada. Her parents and most members of her family were also able to get out of Afghanistan.

However, like most of the 17,000 Afghans who have so far made it to Canada out of the promised 40,000, she constantly worries about close friends and former colleagues she left behind.

Their lives in Afghanistan stand in sharp contrast to Qureshi’s. Her former colleagues who used to work with her for the Afghan government are now unemployed because that particular ministry has been dismantled. She shared the story of her close friend.

“They are a family of 11 and nobody in the family now has a job. They are barely surviving by buying vegetables from a vendor and then reselling them for a small profit,” she said. “My (former) colleague recently had COVID, but vaccinations are no longer available because the vaccine supplies used to come from other countries.”

Asuntha Charles is the Afghanistan Director of World Vision, an NGO that specializes in helping children in need. A native of Chennai, India, she spoke to New Canadian Media from Seoul, Korea where she was advocating for aid to Afghanistan. She is asking various governments, including Canada’s, to place Afghanistan on the “humanitarian plus” list.

She explained that “humanitarian plus” enables not only humanitarian aid but also other forms of assistance to meet emergency needs such as the right to pay health sector salaries.

The European Union already has a humanitarian plus program in place for Afghanistan.

“Canada is not even providing humanitarian aid, let alone humanitarian plus,” Charles said, emphasizing that the stories of suffering in Afghanistan are very real and go far beyond what the World Health Organization and World Bank numbers can tell.

“It is so sad to see children picking through the garbage to find scraps of food, homeless kids on the street and parents selling their daughters for marriage to much older men,” she said. “ Kids are vulnerable to sexual exploitation.”

Charles is one of the few humanitarian aid workers who stayed behind when Kabul fell to the Taliban. She intends to return to Afghanistan in two weeks after her advocacy tour of several countries.

She said she too would like to see the Canadian government adjust its anti-terrorism laws to allow aid organizations to help Afghans living through the socio-economic catastrophe.

A House of Commons special committee on Afghanistan headed by MP Sukh Dhaliwal tabled a report in June this year. One of its recommendations is for the government of Canada to review the anti-terrorism financing provisions under the criminal code and urgently take any legislative steps necessary to ensure that those provisions do not unduly restrict humanitarian action.

In response to a New Canadian Media query, a spokesperson from Dhaliwal’s office said that there has been no government response yet, but that the government can take up to five months to provide one.

Ottawa-based writer/journalist, editor, blogger, communications professional seeking freelance opportunities in political and travel writing.