In 2021, 4.6 million Canadians spoke languages other than English or French at home according to numbers released August 17, 2022 by Statistics Canada. Many of those would be in families that have emigrated to Canada and have to rely on their children to help them acclimatize to their new surroundings, often using them as translators. That’s because children tend to learn English faster than their parents.

As language brokers the children aren’t just translating but often also helping their parents interpret the larger culture around them. Although this practice may be helping the parents become accustomed to their new country, their children are given an added responsibility.

Cecilia Huang is a first-generation citizen. Her parents moved to Canada from Taiwan when she was nine years old. She had to translate official documents concerning her parents immigration to Canada into English.

“It’s an added stress and responsibility,” said Richmond B.C. -based Huang, who is now a mother herself. “It’s almost like as a kid you have certain things you have to do.”

Huang is what experts call a child language broker, and as a child she translated legal, medical and tax documents for her mother, while her father travelled frequently for work.

Language brokering is a familiar experience with first-generation immigrants who access an intimate knowledge of their parent’s health and financial issues by acting as translators.

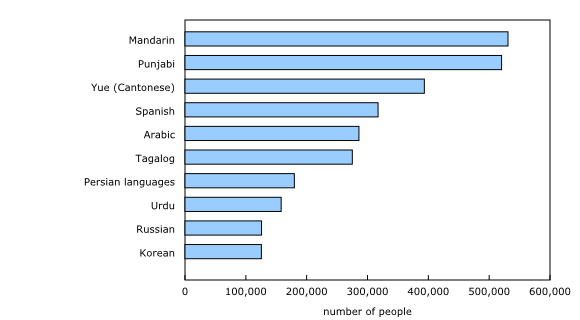

The number of Canadians who speak predominantly languages other than English or French at home rose 16 per cent between 2016 and 2021, from four million to 4.6 million. Mandarin, Punjabi and Cantonese are the most spoken languages in Canada after English and French, according to 2021 census data from StatsCan.

University of British Columbia Professor Anusha Kassan is a second generation Canadian. Her parents moved to Canada before she was born. She studies factors that help and hinder language brokering in children. Kassan believes the best way to navigate this relationship is through communication and making sure children understand what their translation responsibilities are.

For the parents, it can be a hard transition moving to Canada where their children are their only support, Kassan said. There is “an impact on the parents’ own confidence, competence and ego.”

“Having to ask their children for something, when, not long before arriving to Canada, they were the providers,. they were the ones with the knowledge, the ability and the skills, that role reversal can be difficult,” she said.

This creates a unique family dynamic for immigrant children that can follow them into adulthood. Many like Huang still help out their parents when needed.

“I think we’re kind of in that gap generation where we’re taking care of the older generation as well as the young,” Huang said. “And I feel like that might continue to be the trend.”

Even at a young age, this can create an imbalance in the relationship between parents and their children. But, like in Huang’s case, it is bred from access to few choices.

“Most of the time, language brokering is not a choice for immigrant families where there are language barriers,” Kassan said “It’s the only way to engage with society and get to know the host culture.”

Kassan’s research shows children helping out their parents can bring the family closer together. If children understand their responsibility and how their abilities are helping out their family it can boost their self-esteem and confidence.

“One of the recommendations is to be up front with the children about what we’re going to be asking them ahead of time,” Kassan said “As opposed to just showing up at the appointment and then expecting them to do the translation at the same time.

“When they’re old enough to understand [their language brokering responsibilities] they can sometimes feel like they’re giving back to their parents. They’re contributing to the household in a positive way.”

“It could also help children and teens feel a little bit more responsible,” Kassan said.

Both Huang and Kassan agree the best way families can deal with translating English, and the effects of language brokering on their children, is through communication. Parents and children alike have to be able to express how the family dynamic affects them mentally and emotionally.

Prabhy Rehal (She/Her) is a fourth-year Humber journalism student who is passionate about accessible journalism and storytelling. She is a member of the Sikh community and a daughter of Punjabi immigrants. These identifiers also inform her advocacy for social justice as it allows for an empathetic approach to her work and the need for precision in storytelling. As a BIPOC journalist, she understands the importance of hearing every voice and hopes to highlight stories and share the experiences of those outside the mainstream.