Are classroom teachers integrating Indigenous content into their teachings? “What is being taught? How is it being taught? Is it authentic? Does it accurately reflect the true history of colonization?” These are the key questions for history education in Canada, says Gayle Bedard, Tsimshian from the First Nations community of Lax Kw’Alaams (Port Simpson) and district principal of Indigenous education in Coquitlam, B.C.

According to Historica Canada, provinces and territories still have a long way to go in creating history curricula that effectively include diverse narratives. The non-profit’s recent assessment of mandatory history curricula in grades seven to twelve across the country resulted in an average score of 67 per cent, equivalent to a C-.

Mira Goldberg-Poch, manager of programs and education at Historica Canada says “We’re still as a country struggling with how to address the changing perspectives on history and learning … between the pedagogy and the actual content itself.”

A critical focus of these report cards compared to the last ones in 2015 was how well the curriculum addressed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action (62-65) around education.

Lack of integration around reconciliation

Scores among provinces and territories varied widely. Ontario had the top grade at 85 per cent (A+), B.C., the Yukon and anglophone New Brunswick all scored 72 per cent (B-), and Quebec and Alberta were at the bottom with 57 per cent (D+) and 50 per cent (D-) respectively.

The lowest scores come from places where the curriculum has not been recently revised, particularly around the TRC Calls to Action released in the last five years. Goldberg-Poch says that, aside from Ontario, these calls have been included as an “add on” rather than integrated into the curriculum.

This “silo effect” also shows up when schools see the learning that fosters reconciliation and the success of Indigenous students as the responsibility of their Indigenous education departments, rather than being part of the system as a whole.

“Supporting the TRC recommendations in education must come from the top down and the bottom up in every school district,” Bedard says.

Inquiry doesn’t equal critical thinking

Many of the courses emphasized inquiry, but this didn’t necessarily translate into critical thinking.

“A lot of the so-called inquiry questions that are recommended in curricula are questions that are leading and that actually just kind of funnel students to a predetermined answer,” Goldberg-Poch says.

Teachers also have a significant influence on how required skills and content are taught in the classroom. Although they must now cover Indigenous history, “the challenge is how do we become more authentic and more meaningful with teaching this?” Bedard says. “And that’s every single teacher’s responsibility.”

Lack of personal reflection

B.C.’s assessment found that students did not have adequate opportunities to reflect on their learning and connect it to themselves and their communities.

The current practice of land acknowledgements is an example. “It’s become so normalized that people don’t even think about it anymore,” Bedard says. “So how does reading the land acknowledgement connect with you? What does it mean to you?”

School districts have struggled to address the recent discovery of the remains of 215 children found at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. “An elder said it was like Canada was “struck by a thunderbolt” but this is something Indigenous people have always known,” she says. “But nobody listened to or wanted to believe lived experiences such as this could ever happen in Canada.” Bedard’s father is a residential school survivor.

There were comments such as “the children are too young to hear about such tragedies” from educators. Yet last November, Bedard’s granddaughter in kindergarten participated in her school’s Remembrance Day ceremony by laying a wreath. If teachers can talk about wars with their youngest students, why is talking about residential schools such a struggle?

Mandatory content isn’t enough

Anita Movazzafi, a recent graduate from Handsworth Secondary School in North Vancouver, B.C., remembers learning about residential schools in her required high school social studies classes.

“I think it definitely wasn’t enough, because it hasn’t stuck as well as it probably should have,” she says. In contrast to events like World War II that were mentioned in grades 10, 11 and 12, residential schools were only covered in grade 10.

Also, mandatory courses don’t delve into the specifics. “A lot of . . . nitty-gritty stuff and when they show you diverse perspectives (are in) elective classes,” Movazzafi says. For example, discussions of movements like Black Lives Matter only happen in History 12, an elective.

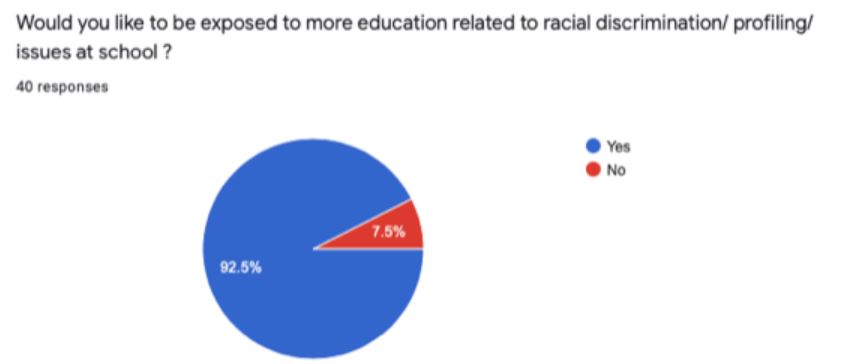

In an Instagram survey Movazzafi conducted on high school students’ exposure to learning about racism in school, 37.9 per cent indicated that the education they had received about racism and racial profiling was in an elective course. “It’s a big enough chunk . . . to be a little concerning,” she says.

Indeed, 92.5 per cent of youth respondents to Movazzafi’s survey indicated that they would like to be exposed to more education related to racial discrimination and profiling at school.

Lack of Indigenous voices

Movazzafi’s social studies classes did not provide an opportunity to hear from Indigenous people.

“I think we might have been able to learn about it better if there were actually Indigenous people coming in and telling us something, like a speaker,” she says, “because lived experiences always stick better with kids.”

Movazzafi did middle school in Edmonton before moving to Vancouver and remembers her grade seven history course more focussed on the culture of Indigenous people than the historical facts.

Young immigrants’ knowledge of Canadian history

While doing presentations on Indigenous history for the Korean ambassador training program, Bedard found newcomer participants eager to learn despite the language barrier.

Born in Canada, Movazzafi is the daughter of Iranian immigrants. She believes what immigrant youth learn about Indigenous history depends on what grade they arrive in Canada, and which electives they then take. This could lead such learning to fall through the cracks.

As most newcomers arrive seeing Canada as a democratic country providing them with the opportunity for a better life, education on Indigenous history is critical. If immigrant youth do receive this education, Bedard says, “They will be allies going out into the world.”

For the first time, Bedard’s district has included Indigenous objectives in the strategic plan, along with action plans for learning, requiring all schools to implement the First Peoples Principles of Learning, so all students learn about the true history of Canada and participate authentically in celebrations such as Orange Shirt Day and Indigenous education month.

Like Senator Murry Sinclair, Bedard believes that education, formerly the main tool used to oppress Indigenous people, is crucial for Canada’s transformation.

Daniela Cohen is a freelance journalist and writer of South African origin currently based in Vancouver, B.C. Her work has been published in the Canadian Immigrant, The/La Source Newspaper, the African blog, ZEKE magazine, eJewish Philanthropy, and Living Hyphen. Daniela's particular areas of interest are migration, justice, equity, diversity and inclusion. She is also the co-founder of Identity Pages, a youth writing mentorship program.