Children of immigrants learn to live in two worlds. As a first-generation Canadian, I learned to maintain and modify my Italian culture in order to make it valid and workable in Canadian society. There is some consolation in knowing that many children of immigrants share this feeling and practice.

As a woman raised in an immigrant home, I travel daily between the rural, southern Italian culture I acquired inside my home and the urban, mainstream Canadian culture I live outside. Each day, I build bridges of understanding, as I create a new culture. This new culture straddles the ‘old’ world in which I was raised and the ‘new’ world of contemporary Canadian society. There is no doubt that the contrast between these diverse realities has allowed me to live a more full life.

As a woman raised in an immigrant home, I travel daily between the rural, southern Italian culture I acquired inside my home and the urban, mainstream Canadian culture I live outside. Each day, I build bridges of understanding, as I create a new culture. This new culture straddles the ‘old’ world in which I was raised and the ‘new’ world of contemporary Canadian society. There is no doubt that the contrast between these diverse realities has allowed me to live a more full life.

My parents were post-war immigrants to Canada from Calabria. My father, Domenico Valle, arrived at Pier 21, in Halifax, in 1957. My mother, Giuseppa Ziccarelli, came in 1960. My parents had been neighbours in their hometown of Lago, Cosenza. My father was the eldest of his family, and shortly after his father died, he went to France, Germany and eventually Canada in search of steady work.

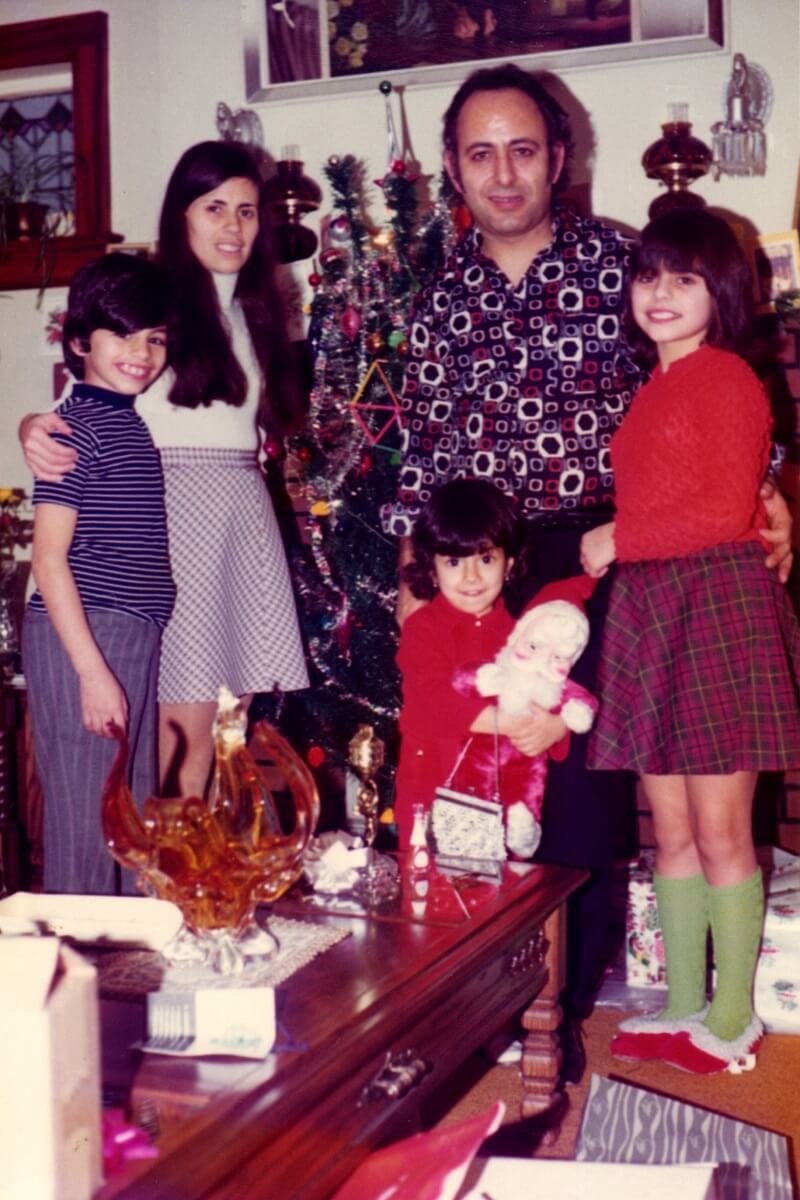

While in Toronto, my father held down three jobs and lived with his cousins, Luca and Sofia Perri, until he decided it was time to get married. He wrote his neighbour in Lago, Antonio Ziccarelli, and asked for his eldest daughter’s hand. A few months later, in the spring of 1960, my mother boarded a ship in Napoli, bound for Canada. (A wedding picture at left)

Two years after her arrival, I was born. Three years later, my brother Antonio Nicola was born. In the early years, my father made donuts, washed cars, and sold vacuum cleaners. My mother made clothes for dolls and took care of boarders, to help support her family. As my parents worked around the clock, my grandmother, Luigina Valle, cared for us in our home. Nonna had come to Canada, to live with her eldest son, shortly before my baptism.

Although my father’s love of building new homes was where his real interest lay, he went on to start a business as an insurance broker, with my uncle Domenico Groe. They worked hard at this business, until they finally retired and closed their doors in 2002.

Richness of two worlds

I attended public schools, and in keeping with my parents’ strong work ethic, I began working as an 11-year old by delivering newspapers, babysitting and stocking shelves at the local drugstore. From time to time, I would adopt a ‘Hollywood’ version of life, but otherwise, I instinctively knew that everything in life would require hard work.

I attended public schools, and in keeping with my parents’ strong work ethic, I began working as an 11-year old by delivering newspapers, babysitting and stocking shelves at the local drugstore. From time to time, I would adopt a ‘Hollywood’ version of life, but otherwise, I instinctively knew that everything in life would require hard work.

Language and culture shape me as they weave their way through my life as a daughter, mother, wife, granddaughter, friend, and professional. Creating a new culture, one that straddles the old world that my parents understand, and the new world of contemporary society, has always been a very complex process for me. As a child of immigrants, I often tried to reconcile the irreconcilable — home and school — my private and public worlds. Many children of immigrants feel that they have to choose between family and school, and this inevitably became a choice between belonging to an ethnocultural community, or succeeding as an individual. This reality caused part of the alienation I have known as a first-generation Canadian. Having said that, however, it also has allowed me to experience the richness of living in two worlds.

Over time, as I learned to accommodate Canadian culture, I quietly abandoned my Italian culture. I believe that this is the reality of many first-generation Canadians, as we struggle to merge two cultures. Immigrants in a new homeland often know only one way of viewing the world. Children of immigrants always know two. Very subtle negotiations became part of my daily decision-making, as both cultures competed for my allegiance. As a teen, I told half-truths and half-lies to get by, like when I wanted to attend the school dance, go to a sleepover, date a boy, wear make-up or travel outside of Toronto. (Picture — family Christmas circa 1970)

The tensions between two cultural systems remain inside me to this day.

Embracing motherhood

It is this conflict that fuelled my professional work, as I continue to search for ways in which bicultural, multilingual children in our classrooms can accept and wholeheartedly believe in their contribution to education and ultimately our society. Ever since I was a child, I made every attempt to be recognized as an impeccable member of Canadian society, which inevitably consisted of closing off my private life when I closed the door behind me and went to school. I became resourceful, as I adjusted my behaviour to respond to the expectations of Canadian culture.

I had to become creative to cope with realities like why there was no summer camp, but rather my holidays consisted of hanging out with Nonna on the front porch. When classmates departed for the cottage, my excursions were limited to the park down the street. I attended university in Toronto rather than moving out and living in residence. Often, I try to make sense of the choices my parents have made, and the lives they have led — dislocated from the old world, alienated in the new. In the end, however, living in two cultures has made me a more flexible, open-minded and resourceful person.

As a woman raised in a traditional culture, I was only expected to wed and embrace motherhood. The added accomplishment of higher education and a profession were niceties. I was often caught between my first culture’s expectations and my own needs and aspirations as a woman. I have had to work twice as hard as the men in my culture, only to receive half the recognition.

In the same year I was accepted to do my doctoral work, I also became a wife. Guess which garnered more celebration? As such, I have lived in a sea of crushing pressure to conform and limit my expectations to that of wife and mother. In other words, I was expected to accommodate marriage and motherhood. Although deeply connected to my culture in many ways, I quietly chose to rebel against the same culture that can devalue our contribution as women. I opted to walk away from the ‘script’ that others had written for me. It seemed, at times, that few of my accomplishments in life were worthy of discussion around the kitchen table.

According to my southern Italian culture, success as a ‘real’ woman is measured by how well I tend to the hearth, and not in academic terms. In the home, I clear away the table and make coffee for my uncles. Outside of the home, I challenge people’s biases and teach immigrant women about their rights. At times, the dissonance between the competing images of womanhood is difficult to shoulder. There is no doubt that many young girls from traditional cultures are attempting to resolve the same dilemma. They need to face their dragons one by one, and with time their courage will surface. Having grown up feeling that few choices were available to me, outside of a traditional female lifestyle, my hope in my professional work is to create a space for young women to consider they have more choices.

According to my southern Italian culture, success as a ‘real’ woman is measured by how well I tend to the hearth, and not in academic terms. In the home, I clear away the table and make coffee for my uncles. Outside of the home, I challenge people’s biases and teach immigrant women about their rights. At times, the dissonance between the competing images of womanhood is difficult to shoulder. There is no doubt that many young girls from traditional cultures are attempting to resolve the same dilemma. They need to face their dragons one by one, and with time their courage will surface. Having grown up feeling that few choices were available to me, outside of a traditional female lifestyle, my hope in my professional work is to create a space for young women to consider they have more choices.

Persevering with French

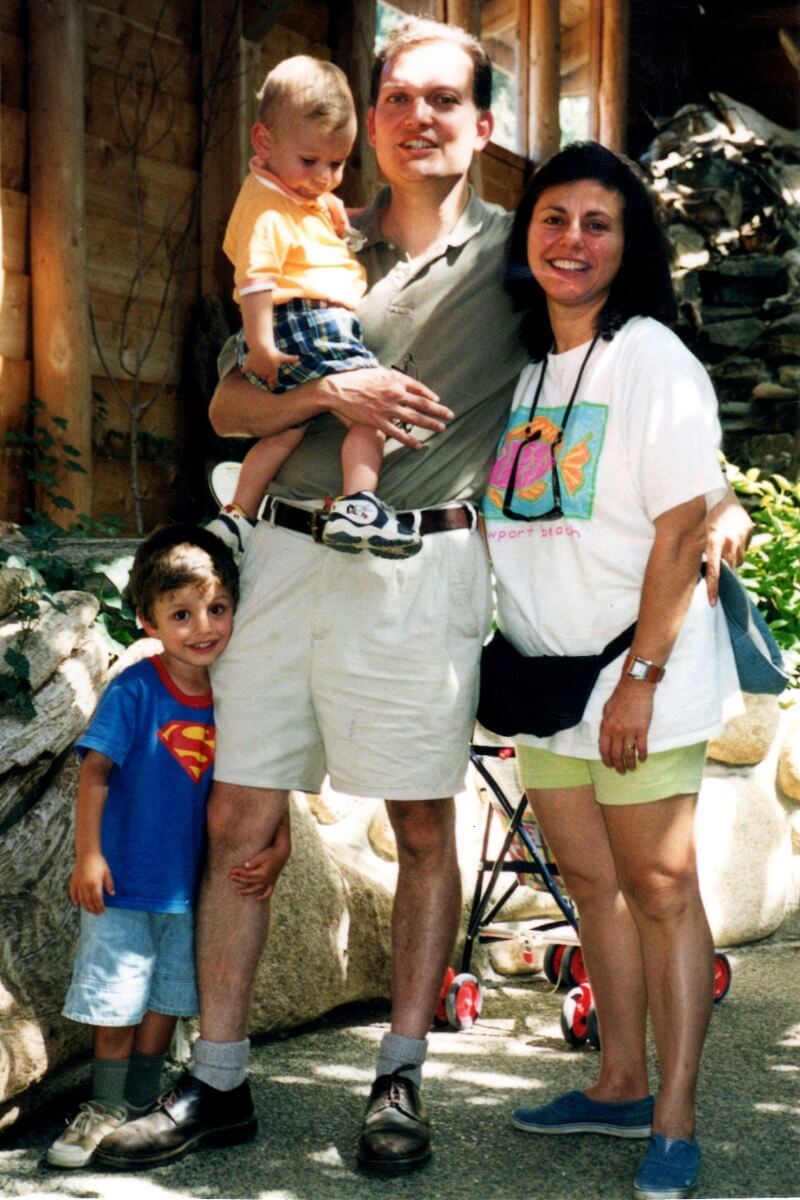

In 1994, I married David Chemla (see picture below) and moved to Montreal where my husband articled and then worked as a lawyer at Stikeman Elliott. We lived there for several years. Prior to moving to Quebec, I had made few attempts to understand the complexities of that province. I quietly settled into my life in Montreal, and went about my business, naturally assuming that Montreal was like everywhere else in North America. I decided that my ‘practical’ commitment to the Canadian debate about Quebec would be to speak French as often as my energy and goodwill would permit. I persevered to gain proficiency in the French language. Over the years, my studies in France, work projects in Quebec, and French-speaking friends and family members all brought me closer to the language.

I arrived in Montreal shortly after the Meech Lake Accord and just before the 1995 Referendum. As a newcomer to the province, how could I possibly grasp the complexity of the cultural and linguistic debates simmering in the province? Gradually, my social identity began to shift. I was now categorized as an Allophone and not an Anglophone, even though I communicate most efficiently in English. For the first time ever, my native origin was questioned by strangers. “I hear a tinge of an accent,” they would say, trying to determine where I was from.

I worked, shopped, entertained, assessed arguments and sent e-mails in French and English. I read, socialized, attended meetings, negotiated car repairs, accessed services, took courses and returned phone messages in French and English. Everything about my life in Montreal was becoming increasingly bilingual. In essence, what is most unique about the city is its inherent bilingual nature.

Our first son, Gabriel was born on a blistery cold January day. It seemed that it would take forever before I would love being a mother. But as routine set in and our son smiled and made us laugh, I fell in love with him and with my new role. My husband David’s work commitments, as legal counsel for a multinational engineering firm, took him to far off places. This meant that I was often alone with a newborn. Loneliness set in and I longed for the days of family gatherings around the kitchen table.

Our first son, Gabriel was born on a blistery cold January day. It seemed that it would take forever before I would love being a mother. But as routine set in and our son smiled and made us laugh, I fell in love with him and with my new role. My husband David’s work commitments, as legal counsel for a multinational engineering firm, took him to far off places. This meant that I was often alone with a newborn. Loneliness set in and I longed for the days of family gatherings around the kitchen table.

I asked David if he could request a transfer to Toronto. He said he would make the request, but he was concerned that our children would not be raised in a French-speaking environment. As a Francophone Canadian, whose family was from France and Tunisia, this was very important. I gave him my word. If we moved to Ontario, I would speak to Gabriel, and then also Alexandre, only in French. I continue this to the present day. Add to that the fact that they attended French schools – their books, television and family chit-chat was in French – and somehow in a sea of English dominance, David and I were able to raise two bilingual Francophone children.

Voice for the community

At some point, their French surpassed mine and it was time to focus on Italian. Gabriel and Alexandre always spoke Italian with my parents. They also attended summer camps, sing-along classes, read comics and watched soccer games in Italian. They developed a strong sense of being Italian, which meant spending time with family, helping the grandparents in the garden or in the kitchen and connecting with their cousins in Italy.

After the defence of my doctoral thesis, which was at the same time that I was carrying our second child Alexandre, my precious Nonna fell ill and it was time to complete the circle of care that she had started when she arrived in time for my baptism in 1963. With two children in diapers, my Nonna bedridden due to a stroke, my husband travelling more than ever since his portfolio had expanded in Ontario, and looking for a decent home in an exaggerated market, my professional goals needed to be put on hold.

They were for a while, until we settled into a routine, in our own home. With the kids in school, given that my doctoral work had focused on Teacher Education and Multicultural Studies, I turned my efforts to working in the field of diversity. I launched Diversity Matters Inc. and went on to publish several books, curate a photo exhibit that has travelled to Scandinavia, Asia and the Middle East, produce and direct a multi-faith documentary, develop curriculum resources and deliver workshops.

They were for a while, until we settled into a routine, in our own home. With the kids in school, given that my doctoral work had focused on Teacher Education and Multicultural Studies, I turned my efforts to working in the field of diversity. I launched Diversity Matters Inc. and went on to publish several books, curate a photo exhibit that has travelled to Scandinavia, Asia and the Middle East, produce and direct a multi-faith documentary, develop curriculum resources and deliver workshops.

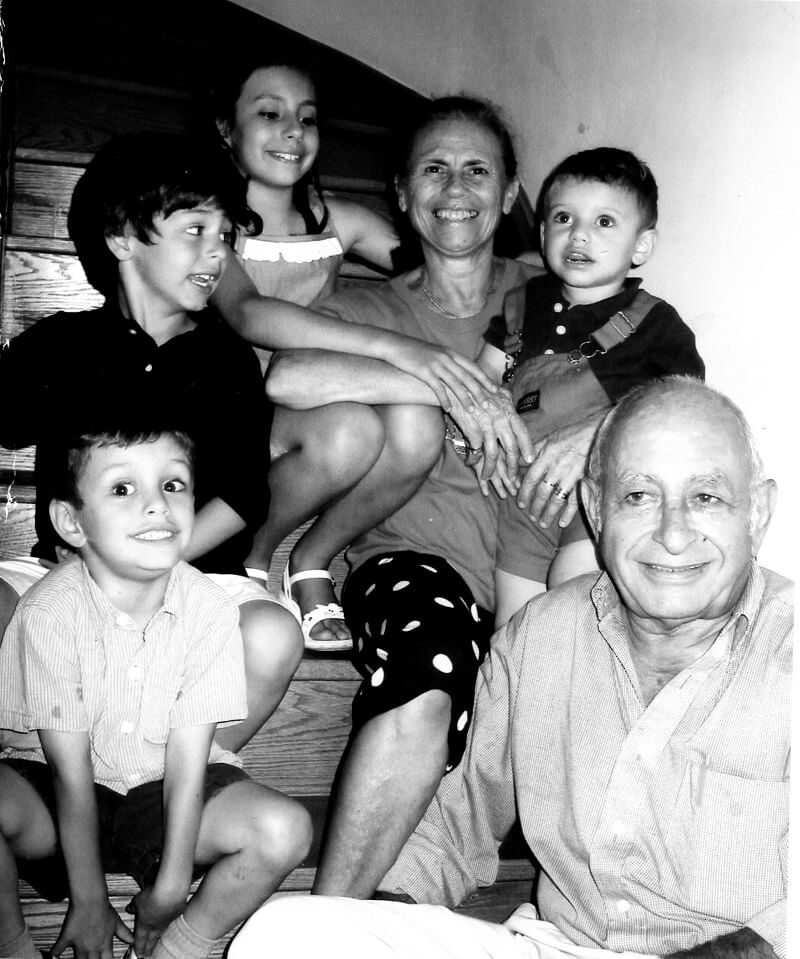

Life seemed manageable, and as decent as it should be, given the storyline we are fed in our noisy world, until the sudden illness of my father. At the age of 74, he was diagnosed with stage four cancer. Dad was the eldest in his family, the caregiver, nurturer, relentless worker who loved his home-made salami, trips to Florida, bocce games, lunch at the Mandarin, and above all else, his family. He died within a matter of weeks, and everything I knew to be true and real, shattered. I grieved longingly for the person who had been such an inspiration in my life, and an exceptional role model for my sons. He left us too soon. (See picture of Domenico and Giuseppa Valle with their grandchildren, in 2004.)

So, instead of having quiet dinners at home or buying a new rug that matches the living room furniture, I participate in a host of Italian Canadian initiatives, from documenting the stories of Italian immigrant women for the Multicultural History Society of Ontario, to providing feedback on the Italian Canadians as Enemy Aliens national project, or being a board member of AMICI Museum, the Association of Italian Canadian Writers, Italian Heritage Month and most recently Villa Charities. I am a voice for our community as OMNI Television restructures its programming for ethnocultural communities.

I help with homework, prepare dinner, carpool to soccer practice and go to a meeting in our Italian Canadian community (or to Lifeline Syria, Multifaith Toronto, or the Canadian Race Relations Foundation). I do this for my parents, and I do this for my children. I do this for Domenico and Giuseppa Valle, as it is my small way of honouring my parents’ love and commitment to us and to this country. And I do this for my sons Gabriel and Alexandre, as it is my way of teaching them about the past, and giving them a strong sense of belonging to a place we all call home.

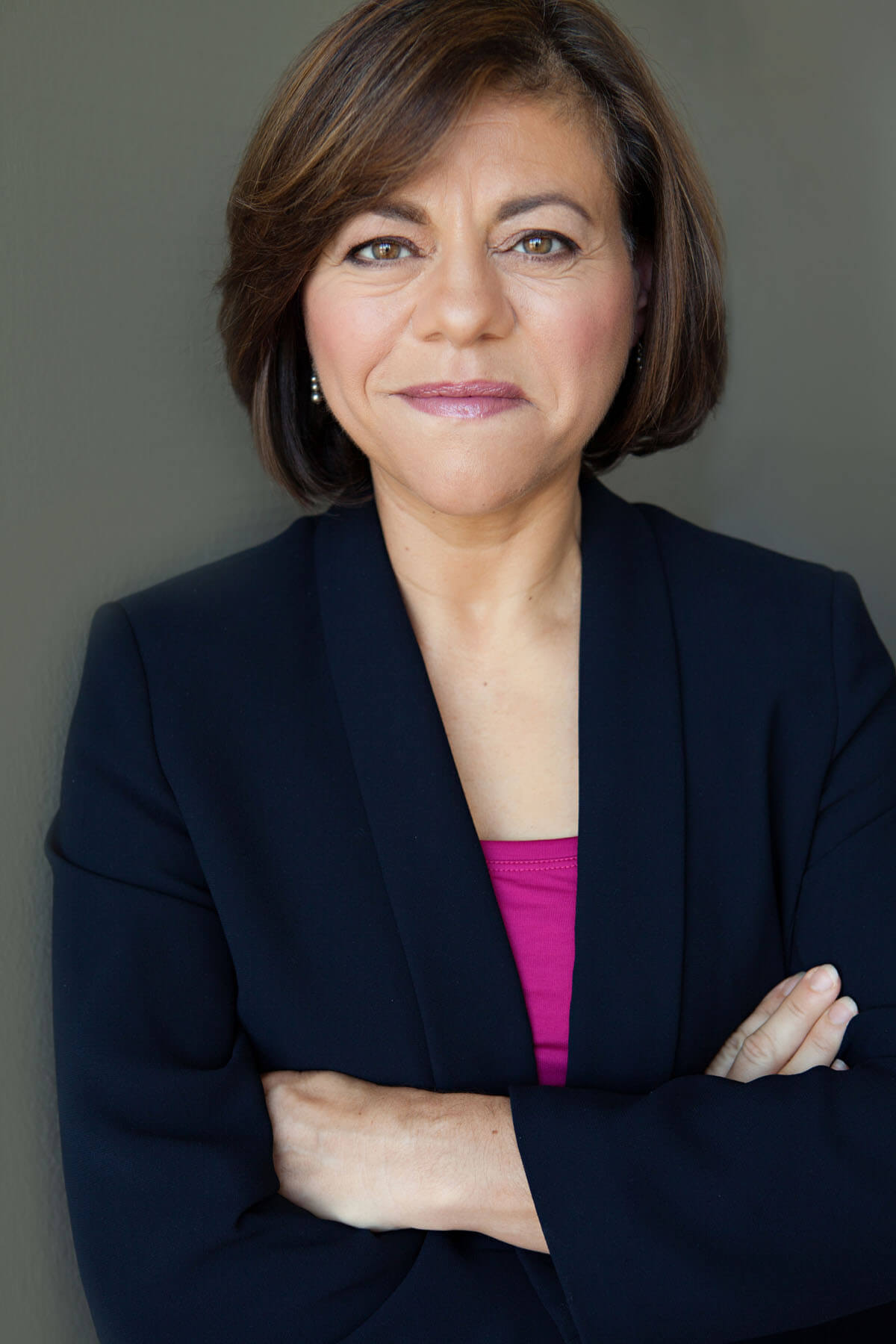

Gina Valle, Ph.D., is a diversity trainer, speaker, author and the founder of Diversity Matters, where she challenges Canadians to think outside the black box when it comes to pluralism within our borders and beyond. This first-person account first appeared in Transformations Canada