Canada is not the land of fairy tales. It is a land of opportunities, welcoming those who are daring and rebound from their suffering – people like Carmen Aguirre, a “revolutionary Cinderella,” whose dreams of being a theatre actor were shattered and rebuffed.

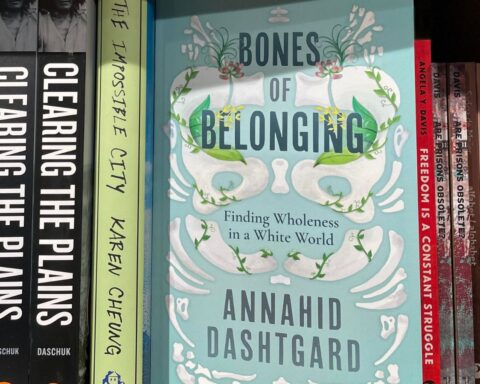

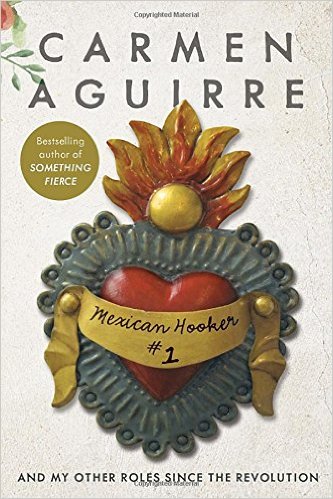

Her journey from a five-year-old refugee to an award-winning actor and playwright is depicted in her memoir, Mexican Hooker #1: And My Other Roles Since the Revolution, with immense audacity and the flavour of fervor.

Young Aguirre escaped the 1973 coup d’état in Chile, which led to the death of President Salvador Allende, and moved to Canada as a refugee with her family.

“Political violence was a concept that I got; senseless violence left me with nothing to excuse him with,” she writes, referring to the man who raped her when she was a teenager in Vancouver, B.C.

“I had no idea that having machine guns pointed at me at the age of five would in some ways pale in comparison with the up-close-and-personal, full-frontal assault of a rape, with having the coldest human I’d ever come across put a pistol to my temple with a steady hand and whisper, ‘Don’t move, or I’ll shoot,’ in a mechanical voice.”

“I didn’t know one doesn’t get over childhood rape, one simply learns how to integrate it.”

Facing her trauma

Aguirre was 13, and her concept of love was not more than “abstract ideas.” She never thought about the “nuts and bolts” of the situation. She describes her physical pain as so excruciating that she believed the man raping her was using a knife.

“I didn’t know one doesn’t get over childhood rape, one simply learns how to integrate it,” Aguirre writes. Her fear was so traumatic, that it hijacked her future love life and profession.

“I didn’t know one doesn’t get over childhood rape, one simply learns how to integrate it,” Aguirre writes. Her fear was so traumatic, that it hijacked her future love life and profession.

Many times, in a haunting style, she describes how John Horace Oughton, known as the “Paper Bag Rapist,” hid his identity and covered his victims’ faces. Oughton called the young Aguirre a “hooker” because she wore a white wraparound skirt and called the rape “making love.”

Yet Mexican Hooker #1 is not depressing at all. It encourages life and the ability to rise beyond the reality of pain and oppression.

The book exposes an awesome experience of a human spirit that marvels at different forms of decadence and viciousness.

A warrior to her core, Aguirre went back to school the day after the rape, despite the fact that the serial rapist was still at-large. Her father urged her to stay home and rest, but Aguirre writes that she did not believe she was sick.

She never wrote to her mother, then in Chile, about the rape until 16 years after the incident. That was the first time she shed tears over the loss of her innocence.

Oughton was caught in 1985 after sexually assaulting nearly 200 victims. Aguirre attended his parole hearings with other victims and developed a “new-found sisterhood” with the other women.

In a direct conversation with the serial rapist, she told him that he taught her “compassion.”

The book exposes an awesome experience of a human spirit that marvels at different forms of decadence and viciousness.

Finding her spotlight

“[I]n this country, white was certainly a colour, and it held all power.”

Aguirre writes about being caught off-guard by racism early in her acting career in Canada and the United States.

“First of all, I had never heard the word Latino until I got to San Francisco, which was looking to me more and more like the thorns of a rose rather than the petally part.”

At theatre school in Vancouver, Aguirre was one of the only people of colour in her program, while “mainstream Canadian theatre presented overwhelmingly white, middle-class stories.”

Casts were typically white and roles open to actors like Aguirre were often racist, such as the role of Mexican hooker or Puerto Rican maid.

“You don’t have what it takes to be an actor,” she was told. “We’re letting you go.”

“After the show, immigrant Canadians from every corner of the globe waited to tell me in broken voices, how much they identified with the character and her story.”

Aguirre transitioned to playwriting, but realized that transforming a personal story into a universal experience could only happen after healing. Ultimately, she found refuge as a workshop facilitator with Theatre of the Oppressed, where she works with marginalized groups to create interactive and empowering theatre.

All her years of training and acting classes since the age of eight eventually paid off in the form of her play Chile Con Carne, a hailed success. The play is a dark comedy about the trials and tribulations of an eight-year-old Chilean refugee living in Canada in the ’70s.

“After the show, immigrant Canadians from every corner of the globe waited to tell me in broken voices, how much they identified with the character and her story.”

Aguirre is now a Vancouver-based actor, playwright, and two-time memoirist. Her first memoir, Something Fierce, tells of her experiences in the Chilean resistance and won CBC’s Canada Reads in 2012. She has written or co-written 25 plays – three of which, Blue Box, The Trigger and Refugee Hotel have also been published as books.

Tazeen Inam is passionate about both print and electronic media. She has a master’s degree in mass communications, has worked as a senior producer and editorial head at Pakistani news channels and has contributed to BBC Radio Urdu in London, England. Inam is presently pursuing a course in digital media studies at Sheridan College.

Tazeen is based in Mississauga and is a reporter with the New Canadian Media. Back in Pakistan where she comes from, she was a senior producer and editorial head in reputable news channels. She holds a master’s degree in Media and Communication and a certificate in TV program production from Radio Netherlands Training Center. She is also the recipient of NCM's Top Story of 2022 award for her story a "A victim of torture, blogger continues fight for human rights in Pakistan"