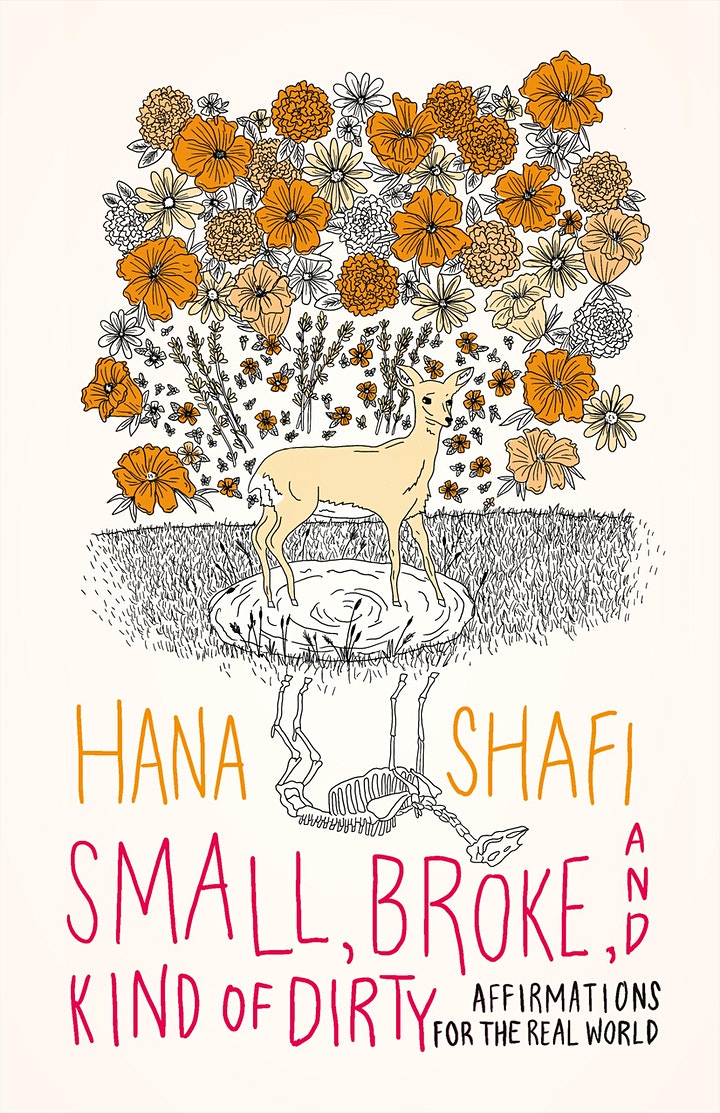

Contemporary life can be categorized as stressful, unpredictable and overwhelming — and that was before the pandemic. And while many people would love a straight-forward guide to teach them how to navigate the travails of existence, Hana Shafi’s new book, Small, Broke and Kind of Dirty, is not that guide.

Shafi is an award-winning writer, poet and artist living in Toronto; her family immigrated from Dubai in 1996. In 2017, Shafi began a series of animated affirmations on Instagram under the handle @FrizzKid. Many of Shafi’s drawings and affirmations explore themes like racism, feminism, body politics, and pop culture. She received the 2017 Women Who Inspire Award from the Canadian Council for Muslim Women. Her debut book, It Begins With The Body, was listed as one of the best poetry books of 2018 by CBC Books.

In Shafi’s book, whose full title is Small, Broke and Kind of Dirty: Affirmations for the Real World, she expands upon the popular affirmation series by adding new dimensions. In addition to the striking images and the uplifting messages of the affirmations, Small, Broke and Kind of Dirty also features anecdotes from Shafi’s life. Shafi reflects on her upbringing in her anecdotes, bringing the reader along on a journey into her childhood through the eyes of a self-proclaimed “weird kid.” The essays are intimate, thoughtful and as colourful as the drawings they accompany.

Shafi manages to talk about challenging social issues like allyship, mental health and gender inequality while sharing harrowing moments from her own childhood with admirable levity. Throughout the book, Shafi encourages the reader to maintain a positive outlook on life and to “not let the bastards grind us down.”

But despite the comfort and the outpour of motivation that readers are bound to get from the book, Shafi insists that she is not trying to give advice. One of the beautiful things about this book is that it never feels like Shafi is moralizing to the audience. Rather, Shafi aims to highlight the complicated nature of our modern existence and encourages us to uplift ourselves and each other by practicing self-acceptance and empathy. Small, Broke and Kind of Dirty reminds us to remember our own worth even when it’s difficult to do so.

I had the pleasure of talking to Shafi ahead of the virtual release of her book.

Do you have any personal affirmations that you say to yourself every morning or regularly?

I think the one that I say to myself most regularly but that I’m not the best at following is not to compare myself to others. Sometimes I get my friends to remind me of that because it’s hard; especially with social media you kind of see what everyone else is doing, which can make you feel like you’re falling behind or you’re not good enough or you don’t have that skill. So I have to remind myself that a lot. You shouldn’t compare yourself to others and you don’t even really know what their life is like or what they’re going through. I have to remind myself a lot that there’s enough success to go around. It doesn’t have to be hoarded by one person, and if one person is successful that doesn’t mean that it reduces your chances because I feel that that’s really ingrained in us, that things are all competition and they are always trying to, like, beat the other person out for the big opportunity.

I do remind myself a lot that just because someone else received an opportunity or if you got rejected, for example, for a job or a gig, and someone gets it, don’t worry, you’ll get your chance too at some point, and you don’t have to be resentful of another person’s success, and I have to remind myself of that a lot. Because sometimes if I don’t get a gig, I feel sad or I feel jealous or bitter and I have to kind of check myself in those moments, and that can be really hard.

In your book you say, “I tell stories and words and art that make people feel less alone that affirm people as they are that maybe get them a little riled up about the big picture stuff that really matters in the world.” That sounds a lot like what people have been talking about during the pandemic; with that in mind, what do you think the role of art and artists is during a time like this or in general?

I think that art is inherently political and I don’t like shying away from political messaging in my art. We don’t need apathetic art right now. But we need art that motivates people because the world is in a really bad state and if no one cares, nothing is going to change. We do see the way that symbols and slogans can rile people up, for good or for bad, right? These are powerful things. And I think it is important to use art as a way to not just inform people about things happening in their community or in a global context but also to kind of let people know that, like, even though there’s things that are obviously not completely in our control, we should all be doing, even on a personal or like really small community base level, some type of work to benefit our world, the place we live, in our family, our friendships, you know?

You may not necessarily be changing the entire planet, but when we do community-based things like when we take care of each other, that’s a really radical thing. Because in a lot of ways we’re told that you don’t really need to take care of the collective, there’s this sort of Western individualism of “you just need to look out for yourself.” And obviously, yeah, always look out for yourself and put your mental health and your self-care first, 100%. But we’re seeing it now, especially with COVID, like you tell people, “Hey, you should wear a mask because if we all wear masks, we’re collectively keeping each other safe and we’re stopping people from dying and getting sick.” And you have people literally being like, “No! I don’t want to. It’s inconvenient to me.” And that’s really screwed up. And sometimes that’s the great thing about art, is that it can be unifying in times of great division.

Do you think that your political art makes it easier to have conversations that are difficult and important about these political topics?

Definitely. Not everyone’s gonna read an academic paper about it, that language isn’t always accessible and not everyone is gonna access a New York Times article about an issue. And while I urge people to look beyond Instagram and look for sources and look for critical reading they can do, I understand that there needs to be a stem off point, and I think sometimes when we’re making political art, on social media especially, it can be a really great stemming off point for people to then find other ways to educate themselves. And I find that sometimes too, the art and infographics and stuff some people make use really accessible language, and that’s really great, it’s a great way to help lay out really complicated issues in layman’s terms. And obviously, that can’t be your only source of information, but if you don’t necessarily know anything about an issue, you need to have an introduction that’s a little lighter.

View this post on Instagram

Why was it important for your book not to sound like trauma porn?

I think when you’re a writer of colour or a writer of any marginalized identity, it’s really easy for people to want to hear stories about your suffering. And on one hand, I think it’s important for marginalized people to write about the trauma that they’ve been through and the things that they struggle with because we want awareness on these things and we want people to destigmatize these taboo topics, and to be able to talk really honestly and vulnerably about things that they’ve been through that are difficult to grasp or difficult to swallow. But I also think sometimes there becomes this expectation that when you consume media from a marginalized person, it’s inherently going to be about suffering. And because of that, I find that, like, stories about joy, the healing and happiness and laughter that come from marginalized people are, like, not as prioritized.

I kind of like to compare it to, well, for a while, movies that were considered LGBTQ films were always really sad. Like someone always died in the end or they committed suicide or the couple didn’t end up together, it’s like a tragic story. And I’ve obviously seen some of those sad movies myself, and they’re great films, but people in the LGBTQ community started rallying on social media saying, “What about joyful love stories? Why do straight people get really joyful happy rom-coms, but queer stories are always really sad or violent?” So there is a need for people of diverse backgrounds to share stories of joy because that way readers from diverse and marginalized backgrounds can read it and see that they do have the possibility of a future beyond trauma. Your future is not just going to be trauma and tragedy that white people are going to read to get entertained. You can have these really, really joyful, amazing futures. And we have funny, quirky coming of age stories too, that’s not something that is exclusive to like white people.

So, it was really important for me to create that work because, you know what, I don’t really want to make it, it’s not entirely safe for me to even disclose that many very personal traumatic things about my life and I’m going to prioritize my safety and my well-being here and I’m going to write about things that makes me really, really happy. And I would love, especially if young brown girls, if they read it and they were like, “Oh, damn. We have really joyful stories and our futures are bright.”

I also wanted to talk about your art in relation to your identity as an immigrant. In one story you talk about your first experience at an overnight camp and you referred to it as a “North American white kid rite of passage.” Why are experiences like that, quintessential North American traditions, important growing up as an immigrant?

I think that when you’re a kid, no matter where you’re from, you want to fit in with the rest of the kids and you want to do what other kids are doing. So when you’re here and you’re the minority, and you see all your white friends from school going to camp or doing like Girl Guides or dance, you want to do that. And all my friends were going to these camps, and I thought, oh my god, camp sounds rad. And when we would come back to school in September, they would tell me all these stories of camp and it was always the white kids. The brown kids, we didn’t go to camp. We weren’t even allowed to go to sleepovers, so camp was definitely not going to happen.

I think when you’re a kid, you just want to experience what everyone else is experiencing. And there is that feeling that I think a lot of young kids who are from immigrant families get of feeling alienated or being left out or not being able to relate to certain experiences and really craving to relate to it. And I certainly felt that and I think that that’s really normal for kids to feel.

I want to ask why art and storytelling is important as someone who’s an immigrant in the sense of helping you understand and express things but I don’t want to project that onto you if that’s not something you experienced.

For me, storytelling was always important because it was just what I gravitated to. And obviously, when you have certain unique experiences that may not be considered the norm or the default experience because we definitely see white experiences as default experiences and other experiences as deviant, it’s important that if you have an experience that deviates from that norm, it’s important for you to tell those stories. But I think for me, I’ve just always loved storytelling and it was always kind of something that my dad especially encouraged me to do. We would talk to each other a lot and he would always tell me, like when I would tell him something, to write it down. He always thought it was really important for me to write down my stories, so it was something that I was raised with.

View this post on Instagram

Because the book will be coming out after we’ve gone through all of this COVID madness, what are you hoping that people will take away from the stories in addition to the affirmations that they may have already seen?

I want people to feel refreshed and rejuvenated from reading it because I feel like we’re all sort of experiencing a lot of collective grief, a lot of burnout, a lot of fatigue. It’s been a very rough year for a lot of people. And I don’t necessarily want to encourage people to just tune out and not care about things anymore because it is important that we care, but you also need hope to make caring not so burdensome. You want to be able to feel like things are going to be okay, so, I hope that the book can give people that. And also to come out of it feeling a little better or feeling refreshed to take on the world again.

You started off the book by saying that this is not an advice book, you’re not a psychotherapist or trained and that you’re not trying to give anyone advice, but I can’t help feel that people will read this and it will be a self-help book for some of them and it will help people. How would you feel about this book being part of someone’s mental health ritual?

I mean, if it works for that person, then it works for them. I’m not going to tell anyone you’re not allowed to take advice from this and you’re not allowed to internalize this. If it works for them, that’s fantastic. But I sort of preface it with that because I see a lot of stuff on social media from people sort of pretending to be mental health gurus and a lot of it is really toxic. They tell people advice in this way that’s so sure of it like, “This is what I do, and it’s gonna work!” And I just really, really resent that. I think it’s so unhealthy and I don’t know why people give themselves the authority that they are now mental health experts because they’ve got a popular Instagram. No. I’m only an expert of one type of mental health and it’s my own. So, if people do read this and say, “You know what, this book really worked for me, I’m going to put it in my self-care kit,” that’s amazing. But I also want people to go into this and be like, “I don’t know if I can internalize this. I’ll try my best, but I don’t know if this will work for me.”

The affirmations are also rooted in personal stories. I’m not rooting them in general experiences or metaphors, I’m writing them as things that I’ve literally done in my life. I wrote these affirmations usually for myself first and I’m not trying to speak for a whole group of people, which is why I chose such personal examples.

_________________________________________________________

Small, Broke and Kind of Dirty was published on September 22 and can be purchased through Barnes & Noble, Small Press Distribution, Book Hug press and others. Shafi is also a graduate of Ryerson’s journalism program and has been published in The Walrus, THIS Magazine and Torontoist.

Marcus is a poet, editor and freelance journalist based in Toronto. He currently works with New Canadian Media as an Editor and as a Freelance Writer for ByBlacks.com, The Edge: A Leader's Magazine and The Soapbox Press.